“BEYOND THE GREAT WALL: THE FIRST SURFERS IN CHINA,” BY MATT GEORGE (1987)

Peter Drouyn of Australia was the first Westerner to surf in China, but just a few months later SURFER Magazine organized a visit with writer Matt George and photographer Warren Bolster, plus pros surfers Rell Sunn, Jon Damm, and Willy Morris. George’s story ran in June 1987 issue. This version has been slightly edited.

* * *

10/29/86

SOMEWHERE OVER THE HUBEI PROVINCE, CHINA

It was the turbulence that awoke me. A dull shudder that shook me from the misery of upright airline slumber and into the consciousness of China. Our delegation—myself, Willy Morris, Jon Damm, Rell Sunn and Warren Bolster—had met up in Hong Kong a few hours earlier and had just made the last CAAC flight bound for Beijing. I unbuckled myself from my aisle seat and made my way to the front of the cabin where I knew I could find the rest of the crew—we were the only Caucasians on the entire plane. I found them all glued to the port windows, taking in their first look at China, 15,000 feet below. Through the streaky windows, a conveyor-belt view of the whole country slowly moved past. The Yangtze weaved a khaki ribbon through an immense patchwork quilt of drab browns and olive greens. Ruler straight roads spidered out from little settlements and stretched towards larger townships, and the whole plain was butted up against a star-peaked mountain range to the east that was shrouded in a mist that appeared smoky and ghost-like. Even from way up here, the country seemed mysterious.

We had finally made it. A pack of surfers—upon the invitation of the Chinese Yachting Association—on our way to introduce the sport of surfing to the People’s Republic of China. It had taken us two years to get this far. Months of planning, endless negotiations, setbacks, reams of Telexes and letters. The entire project was nearly shelved just a few months earlier, but luckily an eleventh-hour reprieve came in the form of Bob Roos and his Delta Institute, a San Francisco-based non-profit organization with experience in Chinese-American delegation coordination. By a lucky coincidence, Roos was due to visit Beijing and offered to talk to high-level officials on our behalf. With his help, the SURFER/China Exchange was kicked back into high gear and made into reality.

All the implications of our visit were just now hitting us. We were flying into the crucible of Eastern man’s original civilization—the birthplace of introspective religion, holistic medicine, and spiritual martial arts. This was the stuff of legends that has fascinated the West since the age of Marco Polo. And we were coming as surfers, for chrissakes! I smiled at the outrageousness of it all, and as our plane began its descent.

* * *

11/1/86

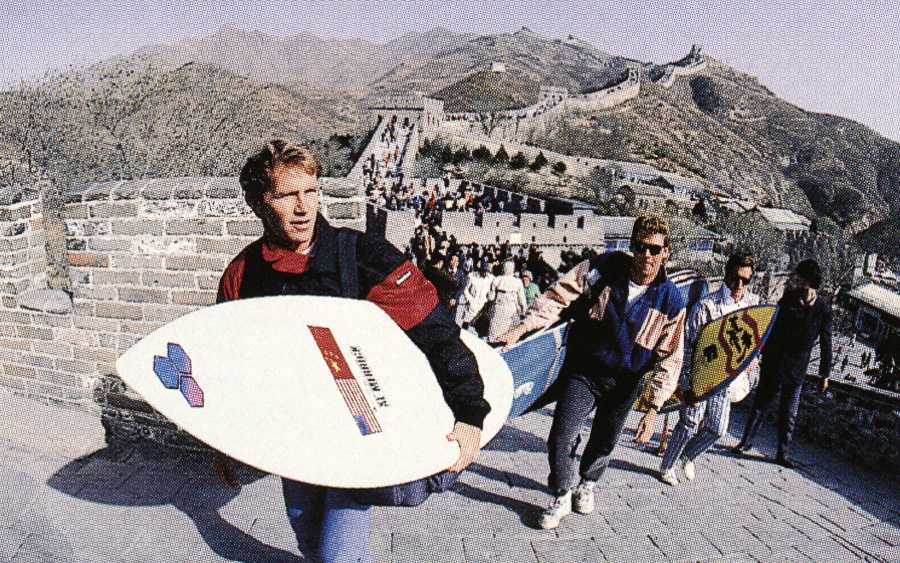

THE GREAT WALL, 110KM OUTSIDE OF BEIJING

A freezing-cold wind tugged at our hair and at our boards as we continued to climb up the only man-made structure visible from outer space. This section of the Great Wall was dizzyingly steep. Our entourage—us and our ever-present translators—had split up and hiked in different directions. We’d brought our boards, as a sort of historic gesture—the first surfers to reach the Great Wall. Willy and I had decided to climb to the north. But to explain our desire to clamber up and out of the tourist throng behind us is to describe our experience with China so far.

We had been met at the airport with the fanfare of a rock group, then hustled into a huge tour bus and put up in the finest hotel in Beijing. For four days we received start treatment, six-course meals, and tightly orchestrated tours of every great sight and temple and holy ground that Beijing had to offer. Our hosts had been unendingly kind, and the sights were impressive. Beijing is a massive cement city dotted with enormous public squares. Rivers of Mao-suited men and women on identical black bicycles pedaled about busily, efficiently. Side alleys teemed with night markets and even more people, droves of them—heavy-jacketed, heavy-lidded people, red-cheeked against the cold of the approaching winter. Occasional groups of soldiers in loose-fitting uniforms of green and yellow could be seen amid colossal temples and palatial grounds—a show force, passive but alert and ready. Bright banners flew from everywhere, along with huge portraits of leaders past and present. This was a vibrant, pulsating city crammed with an ocean of human life that swirled around its ancient temples and new hotels like a tide.

But despite all of this, I felt an undercurrent of emptiness about the experience. And it wasn’t just the fact that we were a thousand miles from any surf. It was a feeling that seemed to permeate everything, wherever we went. A feeling that the outside world had dug itself deep into this country long ago. Evidence of this was everywhere. We weren’t breaking new ground here, or seeing an ancient culture. We were touring well-trod attractions. Site-seeing. The same way as visitors to America take in the Statue of Liberty, the Grand Canyon, Mount Rushmore, Disneyland, and the Golden Gate Bridge, all in one week.

Take this day, for instance. As we pulled up to The Great Wall—the best-known symbol of China’s mystique and accomplishment—we were surrounded by T-shirt hawkers and ashtray sellers and told through a megaphone to use the new handrails. The new steel handrails that had been sunk into the ancient Great Wall of China.

The wind on top of the final rise was freshening as Willy and I plopped down against the protection of a crumbled buttress. A muffled silence fell over us. We were completely alone; there was nobody in sight, and we could hear nothing but the wind. Grass tufted between the cracks in the stones. The Wall stretched out before us, off to the east; a lunging, graceful titanic that ran up and over in concert with the contours of a small range. Like many other structures in China, large and small, it was as if the architecture was designed in scale with the land rather than the human form. It was imposing and extravagant—a reflection of the ancient spirit of the Ming Dynasties.

Willy and I sat there in the quiet and talked for a moment about how badly we wanted to surf. But the view silenced us. I thought back to a conversation we had earlier at the Ming Tombs with an English-speaking Chinese tourist. She said that many Chinese felt that their country had reached its peak long ago, during the feudal ages.

“Our past was a time of great things and of great people,” she said. “All was certain. Now it is not this way, you see.”

Maybe she was right. All I felt now as I gazed out at the Wall and the surrounding landscape was a sense of loss. My surroundings seemed a terribly lonely place; alone and forgotten in its monumental grandeur.

* * *

11/10/86

SPRING BAY, HAINAN ISLAND, THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

Atop one of the gargantuan sand dunes that flank Spring Bay, Jon, Willy and I were basking in the sun—surfed out. The “Thunderdome Kids” would soon be here and the day’s surf school lessons would begin. Down below I could see Rell and Jon, out alone, the South China Sea pushing out some crumbly but decent 3-4′ East Coast beachbreak-type surf.

A gallery of local titanium miners had wandered down from their sand dune shanty town to finally check out all the commotion that had been going on for six days now. Our translators and two reporters from a Beijing newspaper were with them, unendingly amazed that a woman could be out there riding waves along with the men. Warren was over at our ad hoc basecamp, waxing up and getting ready to hit it.

The massive bay was hugged between two rocky headlands, each of which bore the scars of giant surf. The foliage had been flattened or torn away as high as 40′ in some spots. The miners that worked these dunes for titanium spoke of the colossal storm surf of the typhoon season with religious fear. But at the moment, it was hard to believe this place was anything but peaceful—we had long since fallen into its languorous rhythms.

Thankfully, we were hell and gone from the official receptions and banquets of Beijing. We were just surfers again, and the beach and the people had become our friends. As I watched Rell finish up a hot ride to the applause of the gallery, those first few days that had led us to this present state of affairs came to mind.

Just six days ago that we’d been bumping and chortling along in a mini-van, following a narrow dirt track that led to this coast. Trailing in our dust, not far behind, was a green military transport truck carrying our boards and gear. We were getting close, everyone could feel it. We had been in China a week by that point, and now, at last, we were within striking distance of waves.

Our feelings were about the only things familiar to us at this point—the anticipation, the sweaty impatience of a surfari in position to score. Our driver and translators were up front listening to Jon’s Bruce Springsteen tape at high volume. Any pop-music tape with intelligible lyrics was a real prize to our hosts. Willy, Rell and Jon were poring over the map, cross-referencing opinions, making decisions. Warren was in the back, all business, soldier-like, quietly checking his camera gear, loading film, cleaning lenses.

And me, I was staring out at the same kind of Asia I used to see every night on the 6 o’clock news during the Vietnam War. We were jostling along one of the countless levees that bisected the surrounding rice paddies. Along this dusty track we would pass through the occasional subsistence farming settlement, filled with wood-and-mortar compounds, with giant pigs in the road, herds of ducks, naked children, and market stalls with hanging meat and trays of dried rice. Out among the paddies, at what from a distance looked like flowers, were the bobbing white sun hats of the workers as they bent over, knee-deep in their labor, or drove copper-colored oxen before straining plows. A few of the people raised their brown and wizened faces in consternation, judging if our motorized procession meant anything new to their lives. It was a lush, swollen atmosphere that rolled by, in harsh contrast to the energized, music-sprayed confines of the van.

That ride through exotica eventually led us to Spring Bay and its playful shorebreak. Having actually found any waves at all felt great and touched off a couple days of optimistic exploration. But after finding similar conditions wherever we went, we decided to stay put and carve out a comfortable little niche for ourselves in the most protected corner of the bay. With a prevailing cross-shore wind sweeping off the mainland, this geographic protection was essential for surfable conditions.

Our days passed pleasantly from there. We’d have breakfast at our hilltop cinderblock dormitory (pork balls or goat meat, boiled carp, fried rice, warm Pepsi). Then we’d caravan five miles across the coastal range to the bay, hike in, set up camp and “demonstrate” all day. We would return for dinner (usually something that Willy aptly named “Chainsaw Duck,” plus more carp and more warm Pepsi). Out of necessity, we actually developed a taste for this cuisine, especially the duck’s feet. To finish off, we’d then adjourn to the tea room with our hosts and talk long into the night about surfing. They viewed it with the same respect as a martial art and would make nightly reports to the All-China Sports Federation about the progress of the exchange. At some point in the future, China will decide if the nation pursues this sport on an international level. But that was for another day. We were simply research subjects and quite happy to serve in that role.

* * *

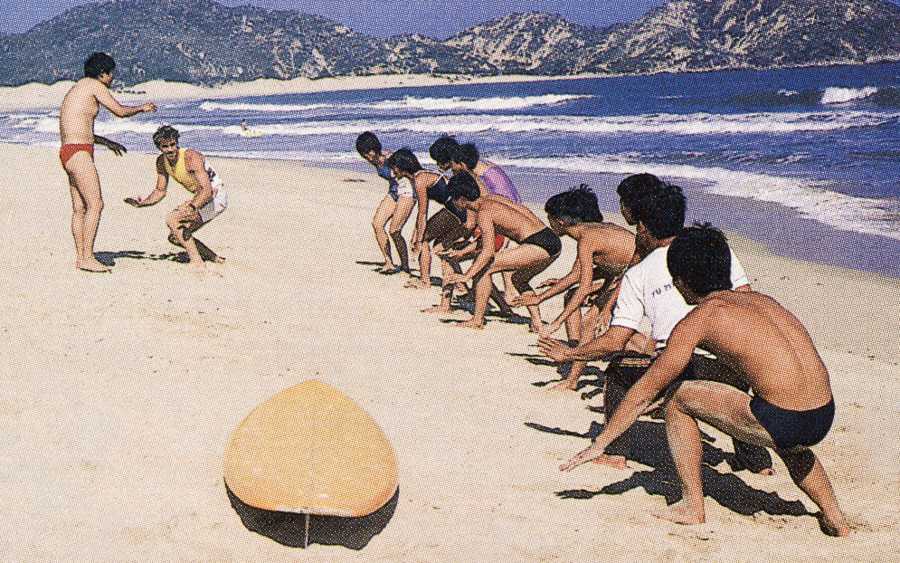

On the third day, something extraordinary happened. We’d just come in from our first surf of the day when up at the top of the path leading onto the sand came a file of marching children. Nine of them. They were in varied stages of ragtag dress and led by a local schoolteacher. To our amazement, five were dragging crudely shaped surfboards. We were speechless as they walked right over and lined up in front of us in completely calm silence. A conversation began with our translators, and the facts were relayed to me. Standing before us was the lost legacy of Peter Drouyn’s visit a few months earlier—a child cadre of local surfers who were introduced to surfing by Drouyn on this very spot. Here they were, nine little keepers of the faith, obediently awaiting instruction and guidance.

We all stood there smiling at each other on some obscure beach in one of the most remote regions left on earth, sharing an unlikely silent bond. Then we all went surfing together.

The days that followed were filled with excitement for all of us. Our “school” was a loosely-organized surfing day camp. The powers of concentration and emulation in our students were astonishing, their commitment frightening. Before long the oldest of them were making regular forays to the outside where they would try to session with us during “recess.” At some point during the week somebody brought a pair of Chinese flags to the beach and planted them in the sand. These standards had lent a certain cultural order to the proceedings—they also gave us something to line up with. At the end of the day they would pull up the flats and march off in single file, completely stoked, having ventured from their isolated world of survival for a few gleeful hours.

I was thinking about all of this at the moment as Jon, Willy and I continued to bask in the sun. My impressions about China, and what we were doing there, remained a jumble—so I abandoned them. I settled, instead, on the hope that despite all the thousands of changes, influences and beliefs the outside world was pressing into China, the spirit of surfing would somehow survive.

[Photos by Warren Bolster]