"OUTRAGING THE CODE OF COOL: ALEC COOKE PROFILE" (1992)

Warren Bolster's profile on Alec Cooke, better known as Ace Cool, ran in the Winter 1992 issue of Surfer's Journal. This version has been slightly edited.

* * *

It was sometime in early 1983 when I first met Alec Cooke. I’d been living above Cafe Haleiwa, and Alec owned the surf shop next door. He was part of radio personality “Surfer Joe” Teipel’s surf report team that included, among others, “Sunset Shelly” and “Kamikaze Kathy.” In return for their efforts, the reporters were allowed a lot of leeway when it came to self entitlements. Cooke, of course, bestowed on himself the nom de plume “Ace Cool.”

I had first become intrigued with Kaena Point in the 1960s when, while passing through Oahu on the way back from Australia, I saw a newspaper story on Charlie Galanto’s passion for attempting to ride Kaena Point, well before the Jim “Wildman” Neece escapades of the 1970s.

In 1983, a year that was to become renowned for its tremendous El Niño surf, I started to wonder what was actually happening out at that desolate, westernmost point of Oahu. The opportunity to find out finally came when, after days of 20–30' surf, a 40' swell closed out Waimea Bay.

I scraped up enough money to charter a small plane out of Mokuleia’s Dillingham Field for a better look. From the air, the potential at Kaena Point looked amazing. The surf that day, while probably not coming in at the precise direction required, revealed an open canvas for new realms of big wave surfing and photography. The normal approaches were getting old, even then.

Shooting Kaena Point, even when unable to linger in the fixed wing craft long enough to see the true layout of the larger sets, breaking about 100 yards off the Yokohama side of the point, was a revelation. With little time left, we flew on to Makaha where it was so big that Buffalo’s prediction of the beach and public bathrooms being swept away was coming true. The waves were undermining the coastal road, and the rip was awash with dirty foam. Apparently, Makaha had either come close to closing out that day or actually had! Only two surfers had ventured out. One was Joe Teipel, on his bodyboard. The other was Alec Cooke.

When I got my photos back, I took them next door to Alec’s Country Surfboards Surf Shop. Alec, by then a well known “wannabe,” liked what he saw and started asking how he could make a name for himself. I kind of laughingly said something like, “Ride this place, no one’s ever documented it. That’ll do it.” I didn’t think he would actually be interested. But the next year we went out in Jeff Johnson’s boat for the ride of our lives—literally. It didn’t help Johnson’s attitude towards Ace when it came time to switch gas tanks off the treacherous Mokuleia side of the point and Alec broke the fuel line.

It was around that time when Alec bragged to surf writer Drew Kampion that he didn’t want to just be part of the big wave riding community. He wanted to be “Chairman of the Board.” The controversy surrounding him got worse from there. In the next breath he was saying he wanted to be like Evel Knievel in the surf! My admonishments to tone it down fell on deaf ears.

* * *

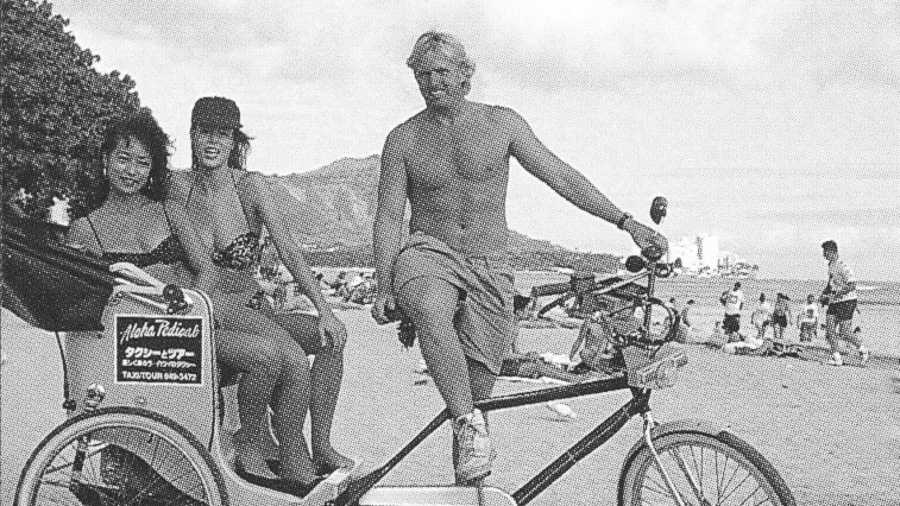

Cooke is 30-something, 6' and 190 pounds. He stays in physical shape during winter by surfing daily and lifting weights. He could bench press around 350 pounds a few years ago, but works more at just surfing and running now. Reports of him along the deserted road to Kaena Point wearing nothing but shoes and socks remain unverified.

During the summer, Cooke operates a pedicab in Waikiki to stay in shape and earn enough money (eight bucks a minute!) to pay the mortgage on his Chun’s Reef home.

As a descendant in a long line of missionary Cookes (as in Castle & Cooke), Alec long ago cashed in his trust fund to pay bills and buy the Chun’s Reef property. At various times, in order to keep the house, he’s turned the property into a youth hostel and a site for impromptu rock concerts. He’s stated that he would rather die than go on living like this. Yet he surfs and lives to this day like his life depends on it.

Sometimes Alec is like a large, friendly-but-clumsy puppy that you have to constantly push off your leg. At other times he can be as abrasive as a boardwalk barker. Which Cooke you have to deal with at any given moment is always the flip of a coin. I still refuse to call him “Ace Cool.”

But before writing this guy off, it’s best to remember that it’s not words, mine or his, that he should be measured by, but actions. What Alec has already done in the surf really hasn’t been touched in recent years, and you never know what he’ll do next.

Should surfing history ignore unique characters and individuals, and record only those events that cater to the most people, or the fewest, or the coolest? You get the point. Surfing is so many things to so many people, and if someone’s view of the sport is offended by the way Alec does things, I’m sure he would be the first to say he’s sorry.

[Note: Cooke rode Kaena Point during a medium-big swell in 1984, with Bolster in the water shooting photos. For this article, Bolster chooses to skip over the Kaena sessions, which did not produce great photos, and goes straight to the surfing event that Cooke is best known for.]

* * *

The early morning light of January 5, 1985, revealed no major swell activity at Sunset Beach during my first drive-by surf check. However, living on the North Shore, especially from the slightly removed vantage point of the Kuilima Hotel, means checking the surf regularly throughout the day if you’re to stay on top of the radical changes in weather and waves this stretch of coastline is famous for. By late morning, another dutiful check was in order, a necessary nuisance to be sure, but one that would prove to be worthwhile.

Over what had earlier been an expanse of subdued blue water, a seemingly endless advance of open ocean swells were now bulging and exploding as far as you could see. Tremendous corduroy lines were graphically sketching the various reefs’ contours—particularly third reef Rocky Point, easily visible from the beach at Sunset despite the gathering ehukai (sea mist). It had suddenly jumped in size from six feet to well over 25 feet and was still climbing. The view from Comsat Hill must have been incredible, but there was no time for that now. As Alec Cooke and I had years earlier agreed to chronicle his attempts to find and ride the biggest wave ever, I set out to locate him and try to get ourselves geared up for what appeared to be the best opportunity we’d had so far.

After pounding hard on his door, Alec finally emerged, bleary-eyed and sleepy—he’d gone back to bed after the early surf report, having had a long, hard night at a rock concert. I rousted him, “Get up! Sunset’s closing out, the outer reefs are going off!"

"No way, I just looked at it,” he said, disturbed at the intrusion and from lack of sleep. Only after his neighbor seconded the alarm did Alec come outside to check the now gargantuan swell. I can't imagine how he must have felt, sapped of strength, to what was obviously a life-and-death situation.

There hadn’t been anything like this swell since the El Niño of '83, and even then, I don’t remember seeing the outer reefs show themselves like they now were. The bay at Sunset was completely overloading with swell action and heavy-rolling whitewater. As it was already midday, just getting the helicopter out from Town would be an organizational problem—neither of us had the money on such short notice for what would undoubtedly be at least two or three hours of flying time.

A quick call to Royal Helicopters’ pilot-owner Ron Thrash (a great pilot, now deceased following a tragic mechanical breakdown off Waikiki) and we lucked out—the copter was available. Ron had been on alert for this project for some time and would take a half payment up front and the rest later.

Considering that by now Kam Highway driving toward Haleiwa would be a North Shore version of the L.A. freeway at rush hour, we rushed to the nearest ATM, at the Polynesian Cultural Center. Money secured, we arranged to have Alec’s videographer meet us at the small landing pad at the Pupukea Fire Station. The helicopter touched down soon after. Making room in the copter for everyone, plus all the equipment, created further chaos.

Ultimately, Alec had wanted to employ a rescue-retrieval system (at least a rope with a tire at the end to be attached to the helicopter), but time had not allowed for even such a basic option. He’d have to paddle in, or in case of a broken board, swim in.

Right now, the thought of getting back to the beach after the feat didn’t seem to be of primary importance to Cooke. The immediate concern was how to get Cooke and his 10'6'' Brewer gun into the lineup.

To the amazement of all around, we slid the behemoth board through the removed rear side doors of the copter, leaving both ends of the beast protruding out each side.

We took off with Cooke and myself in the back, holding on to the board, secured with our arms and legs against the rotor wash and strong trade winds.

As none of us knew much about the North Shore's outer reefs, only having seen Greg Noll’s attempt in '64 to surf outside Pipeline’s lefts, we slowly flew out and then edged over the lineup. We covered the entire reef area from Third Reef Log Cabins to Third Reef Rocky Point, not so much paying attention to landmarks ashore as trying to find a consistently shaped and rideable area. Finally, Alec just decided to go out at some point around Third Reef Pipeline, about 1.5 miles from shore. Tossing his board out, Cooke stood on the copter’s skids pointing down to show our pilot where to drop him off. The board, meanwhile, having been fanned and flipped by the rotor wash, was drifting away. With no further hesitation, Cooke jumped and was in the ocean, swimming toward his board.

Cooke then looked up and yelled for his wax. With everything going on, one of the most basic essentials to the act was missing! But no problem, I thought, and with a quick flick of the wrist I tossed him a bar of Sex Wax without so much as a second thought.

In an instant a loud “clunk” shook the whole bird, and for a split-second the rotor blades seemed to miss a beat before thumping again with their usual deep rhythmic sound. I’ll never forget the look on Ron Thrash’s face as I sunk back into my seat, cringing inside. I had thrown the disc of wax laterally and the jet-propelled blades had sucked it up and caught it full force. As the blades are lightweight and hollow, it could have been a disastrous ending.

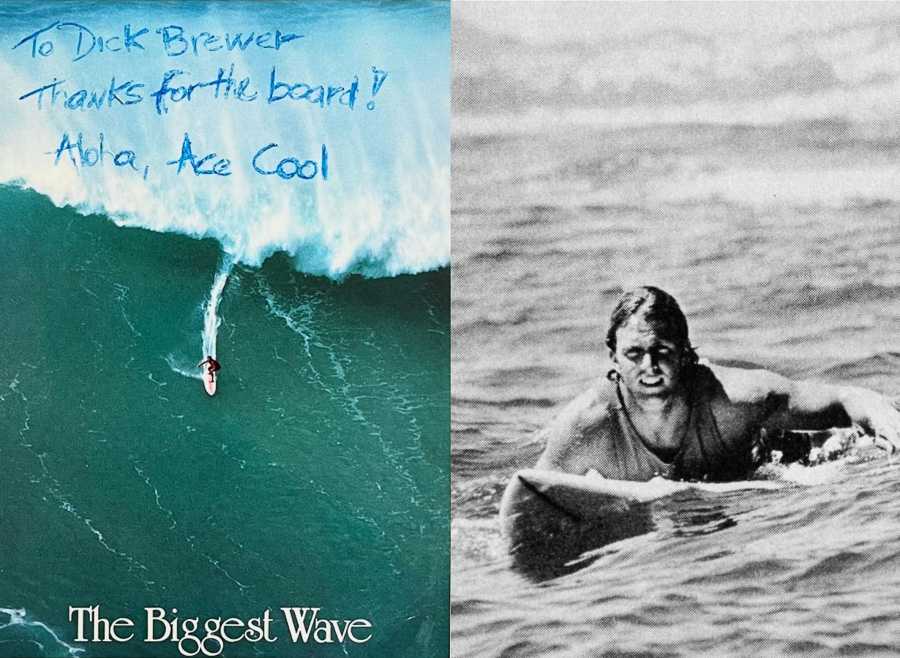

We set about following Alec along the outer edge of the reef. I’m certain he paddled the full length of the outer reefs, over a mile back and forth, trying to figure out the best approach. After his hard night, I can only imagine the effort it took to overcome the pronounced tradewind chop. Finally, after a successful but not-inspirational ride on a lesser wave, Cooke turned picked off the biggest wave we were to see that day. In fact, it was the biggest wave we had ever seen somebody try and ride. The audio recorded was incredulous. The voices inside the copter were a testament to the remarkable feat. Our pilot Thrash, a Vietnam War veteran, was as disbelieving as any of us. None of us could believe Cooke even caught the wave!

I’d lost my only waterhousing and motordrive at big Pipeline the previous month, so I had to hand wind each shot and still managed to get off 19 or 20 sequence shots of the wave as Cooke rode across and then straightened out in the soup. The brief video shot from the opposite side of the copter over the pilot’s shoulder would be played later on the local CBS affiliate.

Although Cooke would stay out for another two hours, and caught at least three more waves, that single ride would remain “the one.” Jetskier Frank Ramos saw us from the Shell Station at Sharks Cove, and thought there was a rescue going on. Ramos came out on his ski to see if he could aid Cooke, but once he realized what was going on, he stayed on attempting to tow Cooke back out and locate his lost board after a wipeout. One long sequence showed Ramos circling Cooke as he paddled back out, unable to help him in the face of one of the massive closeouts that cleaned Cooke out that day. Another closeout set had Ramos racing full speed, with Cooke hanging on behind, across a left to successfully escape an impending larger set outside. On this particular day, we saw no rideable lefts. Everything was breaking right, and there seemed to be no set channels. Outside Log Cabins does have a channel, but Cooke had been unwilling to wait for the larger sets there as outside Pipe seemed to be getting the most consistent size. After several closeouts, with Ramos able to offer only limited assistance, he stopped the circling and headed in, leaving Cooke to face still another giant set.

* * *

Beyond catching and riding that one big wave, the most impressive aspect of Alec Cooke’s feats are of a physical nature. Most will remember him being one of four people out when a monstrous 40' wave broke outside Waimea Bay, in early 1985, cleaning everyone out. After that wave, Cooke who refused the helicopter pick up, preferring to try and swim through the deadly Waimea shorebreak. A truly insane proposition, as the water rushes out faster over the shallow sand than it breaks coming in. Cooke did finally accept the lifeline from the copter that day, but only at the last second as a wave grabbed him, and only then narrowly hanging on for his life.

At Third Reef Pipeline that big afternoon, we watched in horror as Cooke repeatedly continued to paddle his board toward massive closeouts and wicked whitewater stacks, and even attempted to roll his way through. He was quoted later as saying on one wipeout he was under so long and so deep that everything went black. I remember timing that wipeout by my watch (starting after he had already been under a short time) at 20 seconds. We were directly overhead when he came up gasping for air, and I remember being able to look right down his throat. Perhaps after all the stories over the years, 20 seconds doesn’t sound that long, but when you’re being ripped apart, tumbled and thrashed, and don’t know when it will stop, it is a very long time indeed.

After Frank Ramos left on his ski, and the wipeouts and the subsequent loss of board continued, pilot Thrash used the copter to pinpoint the board’s location for Cooke, as well as use the prop wash to blow it slowly back out. (The Third Reef waves backed off into deeper water inside.) We'd been up for two hours by this time, and the helicopter was getting low on fuel, so we had to leave. All we could do was let Alec know and wave goodbye!

The only way in now for Cooke was to either paddle or swim directly to the beach at Log Cabins, or attempt the long paddle to Waimea Bay. As the Log Cabin’s reef is in a league with the nearby and notorious Pipeline, getting to the beach in one piece there was a terrifying proposition.

Cooke later told me he had decided to paddle in, but got cleaned up and had to try to use the bodysurfer’s trick of timing his dip under the wave’s curl to avoid going over the falls. Apparently it didn’t work as planned, and he got cut up a bit for the effort. But he made it. Commented Cooke, “I felt like Robinson Crusoe struggling up the beach.” His huge Brewer gun made it as well—less scathed than its owner.

* * *

Luck. Good old-fashioned luck. Alec Cooke has had a life full, some of the best and worst luck a person can have. For example, a car crash once almost killed him. Reconstructive surgery fixed his half-crushed face.

One Pipeline lifeguard who asked not to be named, but who is arguably Hawaii’s top bodysurfer and a top swimmer, knows Alec from various bodysurfing competitions and says of him, “He’s actually a very good bodysurfer.” While visiting the North Shore, shaper Dick Brewer, himself big-wave rider when he was younger, said this of Cooke, “People put him down, but he’s actually a better surfer than a lot of the big-wave riders of the '60s.”

But how big was Cooke's big wave?

I would conservatively say 25' minimum. But I won't argue with Cooke’s allegation that it was 35'. He’s been in the water on 30' days, and he should know.

[Note: a postcard of Cooke's ride, titled "The Biggest Wave," was a bestseller in Hawaii for years]

Some people continue to say that the helicopter perspective makes the wave look bigger than it is. And it is true that certain heights and angles can cause the face of the wave to appear to have no base at all, as it blends in the flat water ahead of the wave. But it is also true that a helicopter perspective often makes a wave look smaller than it is.

No one is trying to say that Alec Cooke is the only pioneer to hit the Outer Reefs, or the best surfer. But by attempting to draw attention to himself (self-promotion an admitted goal), Cooke put some much-needed attention to a vast area of Hawaiian water that now may be thought of for future big-wave exploits.

It is already happening, in fact. Brock Little has been going out to outside Himalayas, and found other surfers already there! Buzzy Kerbox and Laird Hamilton took Buzzy’s boat to outside Backyard Sunset. Brian Keaulana has used a jetski, now an integral part of lifesaving in Hawaii, to check out Kaena Point for future potential.

Photography-wise, others are trying to capture what we caught that day. They will likely find that the helicopter is one of the easiest ways. There was a bit of bidding amongst various photographers for use of the jetskis this past winter. One plan is to use a ski to race along with the wave. With tradewind chop and the limited speed of the ski (fast as they can be), it’s a risky venture. Out-running set waves was a gamble for Ramos, and even with the equipment improving constantly, it’s still a wild race.

At the time of this writing (late June 1992), Alec Cooke has a 13'2" Willis gun for his next attempt. He’s got three miniature air tanks to strap on his waist, allowing him to breathe underwater—we’ve tried them, and they work. He has even gone out on smaller days with Navy SEALs, in a boat off the Outer Reefs, where they almost got cleaned out by a rogue wave, and the officer in charge called them in.

Another thing we're hearing a lot about these days involves the "buddy system." Alec Cooke goes it on his own. On every project, he’s jumped out of the boat or helicopter by himself with no one else able to reach him should he get in trouble.

People said the waves we photographed of Cooke at Kaena Point in 1984 didn’t look the 20+ feet we said they were. That’s because we simply couldn’t get close enough! Cooke had jumped out of the boat, paddled through the break (with 6- 8" of foam floating all around him), and proceeded to ride waves so far outside that we couldn’t get anywhere near him until the end of the ride. Even then, while riding the same wave, we nearly lost the boat as the breaking wave poured in.

The boat’s owner, big wave surfer Jeff Johnson (not to be confused with Jeff Johnston), had taken Flippy Hoffman and Ken Bradshaw surfing there previously when the waves were said to be occasionally 20'. After our trip with Cooke, he said the waves we witnessed were much bigger, and that he wouldn’t be going there again as, “I’ve got a wife and kids to take care of.”

Alec Cooke hardly thought anything of it. Seems the only thing that really scares him is sharks. We had to abort our most recent helicopter mission at Kaena (and it was huge) because of all the sharks. The Kaena Point-Mokuleia area is a well-known shark breeding ground. Packs of fifty or more have been photographed there. Rell Sunn later that day told me, “People have the wrong idea when it comes to sharks avoiding the surf, they get excited when the water gets all churned up like that.” If we had taken photos that day, without the sharks of course, it would have been historic.

It’s amazing how much punishment a human being can endure and live. I can honestly say in my 45 years of life, and 20 years of photography, I have never seen anything that approaches what I have seen Alec Cooke survive.

Regardless of how large a particular wave is, it seems to me that a much more valid assessment of Alec Cooke’s accomplishments would be best measured by his overcoming what Buzzy Trent once called “increments of fear,” and by his contributing to the discovery and realization of the existence of a whole new realm for advancement and excitement in big-wave surfing.

[All photos by Warren Bolster]