"RICKY," BY DREW KAMPION (1978)

"Ricky," by Drew Kampion, ran in the February 1978 issue of Surfing magazie. This version has been slightly edited.

* * *

I first met Rick Rasmussen on the North Shore in the winter of 1974-'75. He was the United States Surfing Champion that year and was wandering around the country trying to figure out why he hadn't been invited to the major Hawaiian contests the way former U.S. champions had been. He thought it could be because he was the first champ from the East Coast. (From New York no less!)

The following summer, he went to the U.S. Championships in Texas to defend his title and found himself voted out of the competition by fellow finalists, mostly Californians. Last year he was East Coast champion once again, but already he was considering alternatives to the domestic circuit, which seemed to be a closed door. Raz took heed of the new international tour (IPS) and set out on a new and different tack to make it on his own—because chances were that would be the only way he'd ever make it.

* * *

Westhampton Beach, Long Island: where wealthy city slickers bake out during summer. Nearly all the beaches here are private. Large, modern, complexly designed, weathered-wood homes blockade the dunes along the island spine that shields most of southern Long Island from the open ocean. On the mainland side of the island, older, sprawling, more sedate residences hide behind massive hedges on tree-lined streets. The Village at Westhampton Beach is here—with its posh stores, over-priced markets, and quaint little nostalgia trips. Mercedes-Benz' are as plentiful as VWs in Berkeley. It is the last weekend of summer; by Tuesday almost everyone will be gone.

I ride from Riverhead through Quogue to Westhampton in the back seat of Rick Rasmussen's mother's car. His girlfriend, Wendy Lisa, rides in front. Raz is talking a mile a minute; I lean up between the seats to hear.

The big news is that he's been back for about a week, and is heading out again in a few days. He was in Australia, Bali, Java, South Africa, Brazil, and Florida. Home, these days, is just another stopover on the world tour.

* * *

Bill Rasmussen, Rick's dad, is a test pilot for Grumman Aerospace Corporation, and he's currently working with a fully computerized bomber. "You program the target coordinates," he tells me later, "you program the coordinates of where you are. The plane flies you there, the bomb bay doors open automatically, the bombs drop on the target, and the plane flies you home. The pilot just sits there and watches the lights."

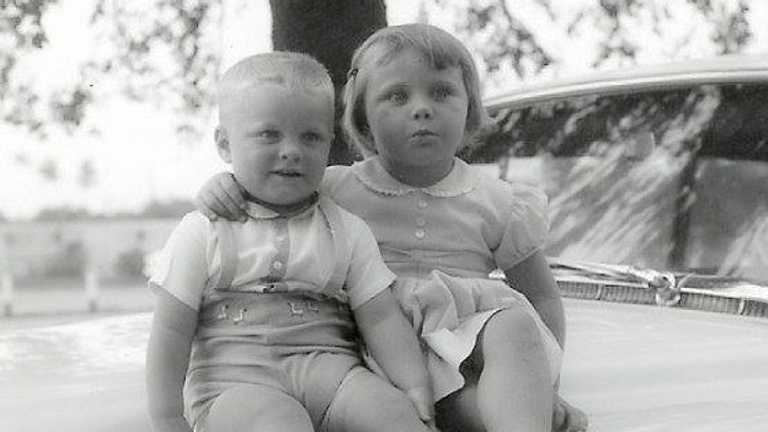

Bill flew helicopters in Maine when Rick was a kid. He often took Rick and his older sister Susan to Sugarloaf Mountain, where they learned to ski. At age nine, was doing advanced slopes. He already loved to go fast.

Joan, Rick's mother, is a terrific cook. For dinner, she served a huge salad, squash, broccoli, shrimp, swordfish, lobster tails, and wine. Bill told stories while Rick and Wendy talked about not mixing squash and fruit because of something having to do with amino acids. They're into health food and are both vegetarians, except for a bit of fish.

The Rasmussen's backyard pool has night lights, and light beer and mosquitoes complete the Eastern evening. Inside, there's an NFL game on TV. Bill switches channels with a solid-state gizmo that shows the channel number for a few seconds before it shrinks away. He shows some pictures of the planes he flies, and of some crashes; his steely blue eyes are hard and light at the same time. He once was a basketball coach; before that he played pro ball.

"Rick and I had our problems for a few years," Bill tells me. "I wanted him to be a ballplayer, not a surfer. Surfers had long hair, and they just hung out at the beach. I told him you have to find out what you want out of life and sacrifice everything else for it—you gotta be dedicated. So one day he said, 'Dad, surfing's what I want to do, and I'm gonna do it.' He's dedicated his life to it, and I admire him for that now. He used to come out of the water in the winter with ice on his eyebrows; he'd take off his wetsuit, throw it into the dryer, jump into a hot shower, and then in a few minutes he'd go out again! That's dedication. I don't know if he's the best in the world, but he's damn good!"

* * *

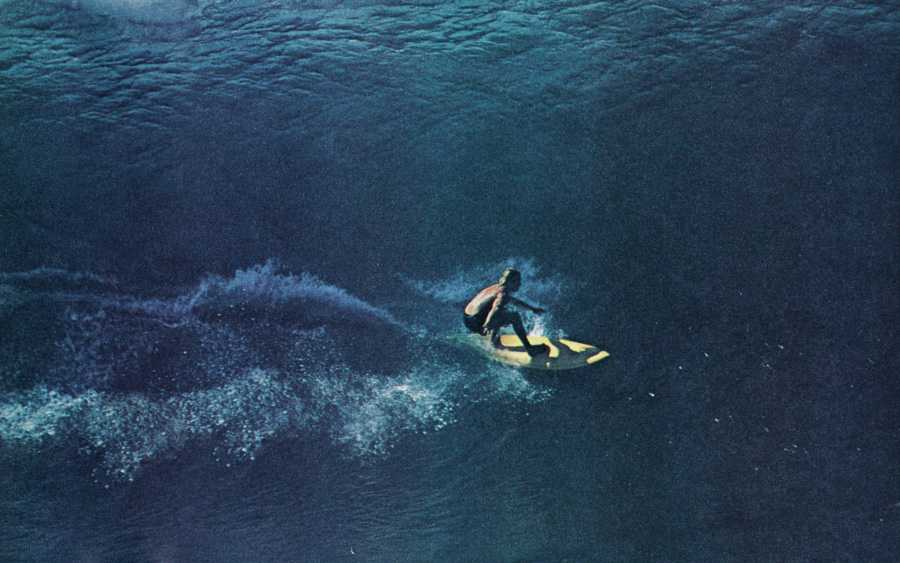

Later in the evening, Rick shows slides of his travels, including many surfing pictures taken by Wendy, who was working with a 650mm lens for the first time. (Look out, Merkel!) The shots were in crisp and well-timed. We saw Rick at Cape St. Francis and howling offshore Jeffreys Bay. We saw him at Uluwatu and at some secret spots around the far corner of the island where Rick and Wendy and a few friends were set up with a lavish Tarzan and Jane tree house, minus the screeching monkey.

"Traveling has totally changed my life," Rick says. "It's put me through a lot of changes really quickly that it would have otherwise taken me a long time to figure out. Traveling is an amazing experience! It's an aging experience, but a good one!”

Bill is amazed that Rick has been around the world already at 22—plus three trips to the South Pacific. He flashes back to Rick's high school days, when the counselor called him in to talk about his son.

Counselor: "Ricky tells me you two play basketball a lot."

Bill: "That's right."

Counselor: "He says you always win."

Bill: "That's right."

Counselor: "Why don't you let him beat you once in a while?"

Bill: "If I did, I'd be the one coming to you."

When Rick's home, he and Bill are on the court nearly every afternoon. Bill, in his 40s, runs the kids in the neighborhood into the ground—and there are some good players around here.

* * *

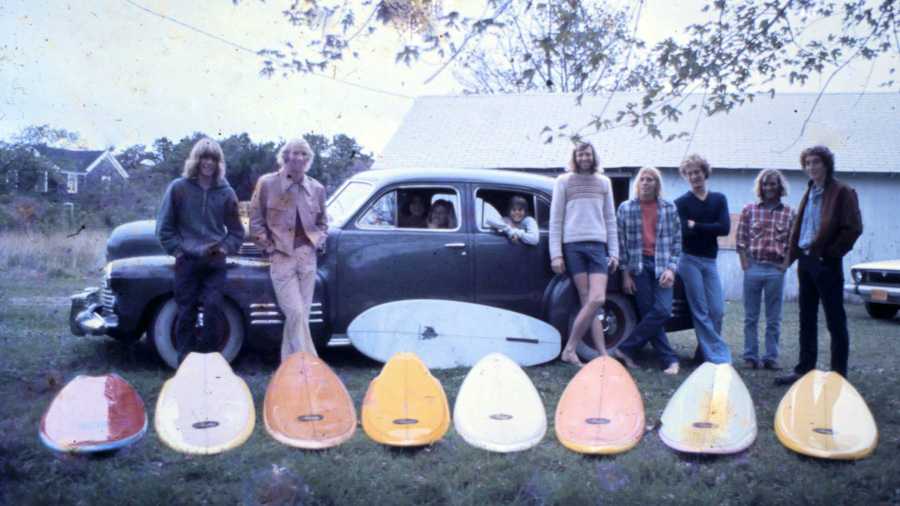

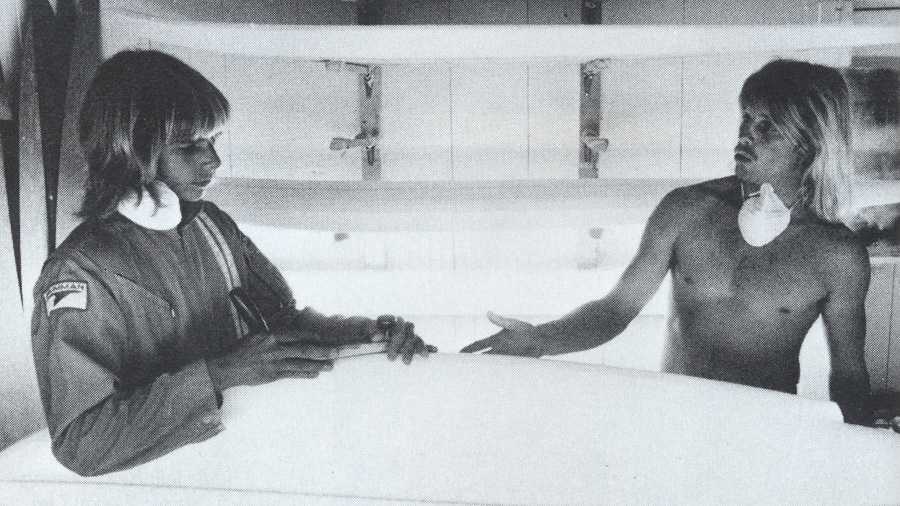

Sunday morning, we drive into Westhampton Village to look for pumpernickel bagels. The surf is flat. The town is sleepy and rich. Everybody seems to know Ricky, wherever he goes— health food store, garage to check on his 240-Z (he also owns a four-wheel-drive Jeep Wagoneer and a '41 Cadillac), down to the strand, where he talks with a couple of local surfers on bikes. Then we head off into a wealthy residential area, into a driveway, and back to a garage that is actually a surf shop belonging to a kid named Michael Schermeyer. Rick taught Michael to shape, and he now works for Rick's Clean and Natural Surfboards while Rick's traveling. Foam dust, blanks, hard pools of resin on the floor, junk everywhere, heaps of old boards, the essence of backyard boardmaking. The surf is flat . . . .

"To be recognized as a good surfer and come from New York," says Rick, "you gotta put out a lot of energy. There are some really good surfers here, too. It's too bad things are so tight as far as attitudes toward East Coasters—but things are gonna open up."

I ask from some names. Rick jumps right in. "Tyler Callaway, Damon Matthews, Joe Fuchs, Michael Schermeyer—they live in Quogue. Eric Penny and Mike Oppenheimer are hot by anyone's standards, and there are plenty of unknown surfers here who're first quality. The East Coast doesn't get much publicity because of the lack of consistent surf, but the surf is hot when it's happening, and I've seen hot surfers everywhere I've been."

* * *

Along the beach between Westhampton and Easthampton is a series of evenly spaced jetties that help create some of Long Island's best waves. Almost anything coming from the exposed south can turn this stretch of beach into grinding green-room country, especially if the wind is a bit northerly. It was here that Rick learned to ride the tube.

"In the beginning, I wasn't really into surfing. My parents got me into it. My dad used to take Susan and me bodysurfing in Maine; we'd hang onto his shoulders and he'd catch waves—pretty big ones—and we'd ride in with him. He'd bodysurf submerged in the white water so that people on the beach would just see two little kids coming in."

The move from Maine to Westhampton Beach from Maine cemented his relationship with the waves: "The more I was into surfing, the closer to nature I got, and the further from society—and my parents—because of their distance from the surfing world. I was a little confused about a lot of things at a young age."

Susan, at first, was the surfer of the family—she was pretty good, but then she spun off into gymnastics and became one of the best in New York state. She was on the Olympic tryout team when an injury took her out of competition.

Speaking of competition . . . watching Bill and Ricky on the court, you see how the competitive drive was passed from father to son: "My parents got me into surf contests," he says, "but it didn't faze me. I dug it! I got free boards. It just kept happening, until one day I was heading out for the East Coast Championships, and a few days later I won. It's interesting—the more I've competed, the more competitive I've become."

Raz shaped his first board at 14. It was 4'10". He still keeps the board in his room. He's made a lot of boards since then under both the Rick Rasmussen and Clean and Natural labels, and his ability (which amazes his father, who says, "He's a craftsman!") has improved steadily over the years under the tutelage of Harold Iggy and the inspiration of Sam Hawk, Owl Chapman, Dick Brewer, and Mike Diffenderfer.

Increasingly, as Rick's traveling takes up more time, the boardbuilding business falls into the hands of those he has trained, but he still gets into it when the opportunity is there: "Whenever I have time and can make a lot of boards, I work out new theories and innovations. But generally I've found that for traveling there's a good conventional trip—roundpins and swallows—nice down-rails with my own bottom contour and rocker design. To me, a surfboard is just the expression of feeling, and I can adapt to anything if it's got a good foil, rail line, and clean bottom rocker. But whenever I'm in one area for a while, I'll get into new, radical designs: stingers, wings, concaves. But with longer waves, you need something for your radical maneuvers and something just to hold you in for the next bowl down the line."

Raz sees himself in the Sam Hawk school in terms of approach and style, which seems accurate, especially in bigger waves. Like the day at Pipeline a few winters ago when it was 10 to 15 feet off the second reef and Gerry Lopez loaned him a 7'5" diamond tail. "I had total confidence in that board. I was on Gerry Lopez’ board! Rabbit, Mark Richards, and I were out first, but it got crowded fast, and I couldn't get any waves. I started to get depressed, then I saw some white water on the outside reef, so I paddled out there. I waited for about half an hour, then paddle for the biggest wave I'd ever seen in my life. It walled up so far, and so fast, when I dropped in I was straight out from Off-the-Wall, and when I bottom turned my heart almost stopped.

"Mike Tomson was paddling out. He told me later that he just freaked; he thought I was gonna die. I ended up getting the longest tube possible at Pipeline. The lip was thicker than I was tall. I didn't know what was gonna happen, and then the spray shot me out of the end, and there was Gerry, paddling out, and his eyes were bugged!!!"

Somehow connected: When Raz won the U.S. Championships in 1974 at Cape Hatteras, he entered the kneeboard contest just for fun, competing against the hot Californians in 4-to-6 foot East Coast tubes. He won and became the 1974 U.S. Kneeriding Champion. "I think, basically, I've been successful because I've been dedicated. Not competitively, but in the sense that I really enjoyed myself. I went surfing all the time because I enjoyed it!"

* * *

For many of the world's hottest surfers, contests seem to represent the clearest path to what people now call “career surfing." But Rick has found the contest path to be more like the contest swamp. "With contests, I've been limited in going to places and surfing the way I like; I've been forced into contest situations, putting out energy and effort and time, but not getting anything out of it.

"I was really disappointed by the thing in Texas [the '75 U.S. Championships] and in Hawaii [not being invited to the big events the year he was U.S. champion]. I mean, that's why I'd accomplished what I accomplished! Limiting those pro events in Hawaii to just one East Coaster [that year it was Jeff Crawford] is not fair to the talents of the people in the East.

"The IPS is making changes, theoretically, but some of the those events aren't too well run either. I was really disappointed with the lack of organization in the IPS contests in South Africa and Brazil. Surfers spend thousands to compete there; you'd expect the people running the events to be halfway organized. When you don't have good waves, it's hard to be organized; they're planned for good surf, and when the waves don't come the system starts to fall apart."

The East Coast surfers' perspective on "organized surfing" must be an odd one. For years, it has been assumed that because the Atlantic waves are sapped of juice by the long, sloping continental shelf, that the East Coast surfer himself must be sapped of juice, too. Or at least he could not be as hot as his Californian, Hawaiian, or Australian counterparts. Jeff Crawford, Mike Tabeling, Greg Loehr, and a few others have pushed back against this idea as it applies to Florida, and Rasmussen has been doing the same for New Yorkers.

Raz is making it where other East Coasters have not made it yet. To some degree, he's involved in the IPS circuit but, more important, he has aligned himself with the global flow—the international surfers. Part of this has come because of his surfing ability; part has come from his "fearless" upbringing; part has come from his ability to respect and get along with people; and a large part has also come from his ability to learn from experiences along the way.

"Everyone I've surfed with, every break, every experience, has been an influence on me. Everything! I'm just a super-open person, and I try to pick up as much as possible. I get along with most everyone. Even when I don't agree with people, their attitudes, I can still get along with them. Being in competition shows a lot of strange things about people, which bums me out, but I guess some people are more competitive than others. Competition, for me, isn't some mental trip; I'm doing it for my future. But I don't feel so much like that now—traveling has opened new doors. There are other possibilities."

We talked about the rivalry between the Aussies and the Hawaiians.

"I can see where the Hawaiians are coming from. I respect them and try not to interfere with anyone else's business. Like, some of those Aussies got what they deserved, and it will be a lot heavier for them in the future. I know 'em all—they're super non-humble gents. But they're just part of the environment they come from. You've seen the pubs . . . ha!"

* * *

Raz has found ways that a surfer can travel and profit at the same time, which is something that a lot of others are discovering, too. Moving from place to place gives a person some advantages, and surfers frequently move from quite civilized, commercialized places to remote, primitive places, then move again to civilized lands. The situation resembles that of the early explorers and leads to some of the same conclusions. Trade, for instance.

Rick brought back over half a ton of merchandise from his last trip to various remote lands, much of it materials and clothing. He had no trouble selling items at various ports of civilization on his way back, at a more than substantial profit. It was something that just fell into place, and now he seems to have the possibility of combining the traveling surfer lifestyle with a bit of international commerce.

"I like to think of myself as being able to compete and being successful in competition, but it doesn't seem like I should have to rely on it for a living. Other things should be developed. It looks like the clothing business will be my main thing in the future—the clothing scam with the incentive of surfing remote breaks."

* * *

The idea of surfing in New York may seem bizarre to some. It seems bizarre to me. But the beach in Westhampton, you know, looks like the beach! And you begin to see that your idea of the East Coast is different from the reality of the East Coast. You see that there are hot surfers coming out of this place; it's even got some hot waves— better than a lot of places with more reputation, although maybe not as consistent.

So Rick Rasmussen stops in to see the folks and some old friends before heading out to more business and pleasure. The mellowed-out, vegetarian, hot surfer from Long Island with the keen head for business and his girlfriend photographer, Wendy Lisa. It's a big world—maybe two people can lick it. Raz sees it as a changing world, with surfing one of the most changing things in it. A new generation is coming in while the old one fades. Only the most dedicated will survive, and no one survives forever. But as Ricky Raz says: "For someone who's come from New York, I think I've got a good shot at it!"