SUNDAY JOINT, 1-14-2024: EDDIE AIKAU IS SPIRITED AWAY AT WAIMEA

Hey All,

EOS will always jump at the chance to go around the world, and this week is no exception. A British surf-mag collector reached out to Julio Adler of Brazil and turned him onto a forgotten gem of a movie by Japan’s Kiyoshi Fujimoto, which closes with a tribute to Hawaii’s own Eddie Aikau, and that film, thanks to Julio, has landed in the inbox of yours truly—feeling Canadian, given what I think may happen next November, but for the moment still identifying as American.

Howzit Bradda! is the name of the film and my Google searches have gone nowhere. No handbill art, no reviews, no IMDB listing. I’m guessing Howzit was released in 1978. Apart from a bit on that year’s Stubbies Pro, in Queensland, the entire movie is shot on the North Shore, like just about every other surf flick released in the 1970s, and the film over-indexes heavily on slow-motion—again, like everything else from the period. The soundtrack, though, is a huge cut above, mostly electronic and often experimental, like early Brian Eno dipped in wasabi, and between songs we get lots of synch sound: you hear the match flaring when mustachioed boardmaker Mike Diffenderfer lights a joint, for example, and a minute or so later we can hear the scratchy but comforting noise of pencil on foam as Mike draws out a template. The general Howzit vibe is that of someone (Fujimoto, presumably) thinking a foot or two outside the surf movie box, and it’s got me hotted up to find more Japanese-made surf films. Turn me on if you’ve got something on the hard drive!

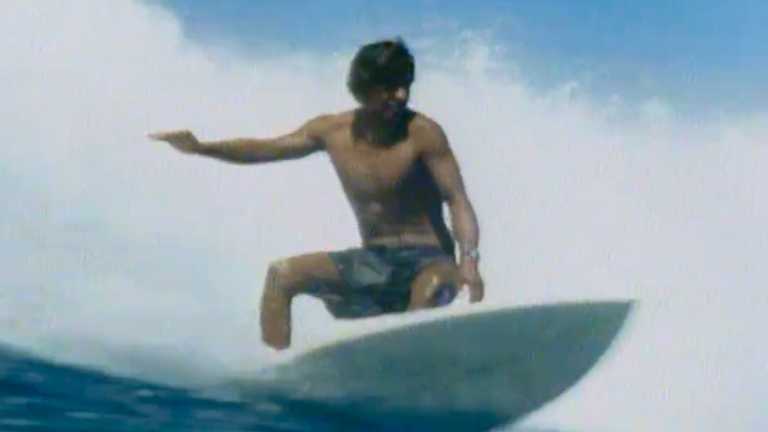

Howzit moves at a languid pace, without narration, and is clearly meant to be an experience rather than anything like a documentary. It’s a stoner movie, basically. But things sharpen up at the end when we see Japanese pro surfer Noboru Sakamoto leap from a helicopter into the ocean. A caption at the bottom of the screen reads, “19, Feb. Waimea Bay (16–18 feet).” We then see Noboru sitting next to Eddie Aikau, who seems to give the Japanese surfer instructions on where to sit and how to line up. The next two minutes is almost all Eddie, same session, riding bumpy smallish Waimea waves with Noboru off to the side taking notes—nothing of real interest here, surf-wise, just a half-dozen waves, all shown in regular motion, and on the last one Eddie hits the deck and prones for shore. Then a crossfade to a birds-eye view of the Holuke‘a voyaging canoe, with the caption reading “25, Feb. Waikiki,” and if you have even a passing knowledge of Aikau’s history you get an uneasy feeling, and for good reason, because what you’re seeing here is Eddie on a shakedown cruise, less than a month before sailing off to his death. I don’t know for sure, but I’d guess that go-out with Noboru was Eddie’s last-ever surf at Waimea.

Next up is a montage from Eddie’s memorial service, also at Waimea. The soundtrack is fluid and jarring at the same time, and more than a little eerie, rhythm-free except for a heartbeat-like percussion, and it’s not a long sequence but it will get in your head, and I wish the entire movie was centered on this beautiful, heartbreaking event. Absent that, we’re left with the Honolulu Star-Bulletin’s front-page coverage, which in itself is a remarkable document. Details jump off the page.

According to the article, less than 1,000 people were on hand for Eddie’s send-off, and judging from the shot below even that number might be high. Aikau was the biggest name in Hawaii surfing at that moment; apart from his tragic and extensively reported disappearance at sea, he’d won the Duke contest just a few weeks earlier. The Waimea service, furthermore, was announced in the papers, held on a Saturday, and open to the public. I’m baffled as to how this beloved native son drew such a small crowd. All I can think of is that the North Shore, in 1978, was still by and large country, and less connected not just to the world outside of Hawaii but Honolulu itself. Plus the service began at 9:00 AM, which is early enough I suppose to reduce the crowd. What else could it be?

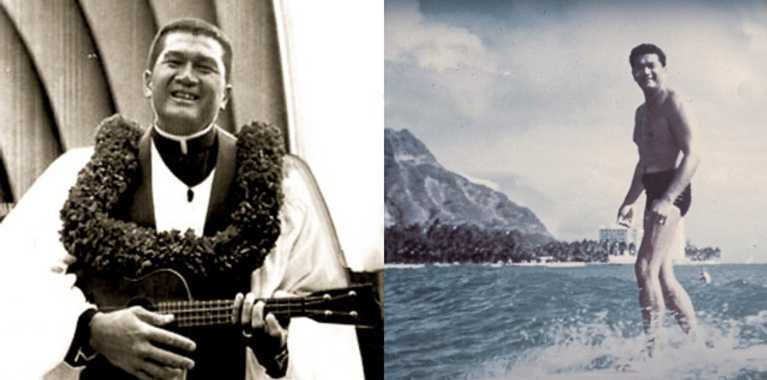

The day was nonetheless filled with notables. Gilbert Lani “Zulu” Kauhi, the beloved comedian-actor-beachboy who played Kono on Hawaii Five-0 was master of ceremonies. Hawaiian Renaissance activist Liko Martin sang his latest, “All Hawaii Stand Together,” which was already on its way to becoming an anthem for the sovereignty movement—over the previous two or three years, Eddie himself had become a sovereignty fellow traveler, if not an activist. Honolulu Mayor Frank Fasi announced, to great applause, that an Eddie Aikau memorial would go up, there at Waimea, in just a few weeks.

But the man of the hour was the Reverend Abraham Akaka, the head of Honolulu’s historic Kawaiahaʻo Church, friend of Martin Luther King, and a first-rate ukulele player who had a few years earlier been invited, uke included, to lead a service at the White House. A generous and prolific blesser of all things Hawaiian—buildings and events, animals, planes, almost anything—Akaka arrived at the Waimea ceremony by helicopter, touching down on the sand after circling the Bay twice, at which point the vestment-wearing clergyman made his way to a makeshift ti-leaf-covered altar displaying photos of Eddie, addressed the crowd, and in the course of a eulogy delivered in English and Hawaiian, declared that the ocean “is the place where people meet God.”

About 100 people took part in the paddle-out ceremony, moving as a group to the middle of the bay where they formed a circle. The North Shore Fire Department helicopter passed overhead and dropped thousands of flowers into the water. There were no ashes to scatter—Eddie’s body was never recovered—so younger brother Clyde Aikau instead swam a ti-leaf-wrapped stone taken from beneath Eddie’s house to the bottom of the bay.

There wasn’t much swell but it had come up slightly throughout the morning, and as the paddlers dispersed a few headed east to the famous point, and Clyde picked up a slightly-overhead wave and rode to shore. Friends and family then caravanned across the island, back to the Aikau home in the hills behind Honolulu, to eat, drink, celebrate, and remember.

The last few months of Eddie Aikau’s life were all over the place, not just highs and lows but extremes on both ends—a long-deferred Duke Classic win; divorce papers back home waiting to be filled out—and as Clyde later said, Eddie was definitely going through some “heavy personal trips.” It was a short and dizzying final act and we’ll get into it more next week.

Thanks for reading,

Matt

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: Eddie Aikau by Col. Albert Benson; Eddie surfing by LeRoy Grannis; Rev Abraham Akaka; the Hokule‘a; Hawaii Five-0 cast, including Gilbert Lani “Zulu” Kauhi, center; Noboru Sakamoto, helicopter jump at Waimea. Eddie on the beach by Benson. Howzit Bradda! title shot. Mike Diffenderfer shaping. Eddie at Waimea, 1978. Memorial service at Waimea Bay. Zulu, right, and fellow Hawaii Five-0 cast member Kam Fong Chung. Reverend Abraham Akaka. For anybody interested in learning more about Aikau, pick up Stuart Holmes Coleman’s indispensable biography, Eddie Would Go.]