SUNDAY JOINT, 11-19-2023: ALOHA AND THANK YOU, STEVE MASSFELLER AND MIKE MOIR

Hey All,

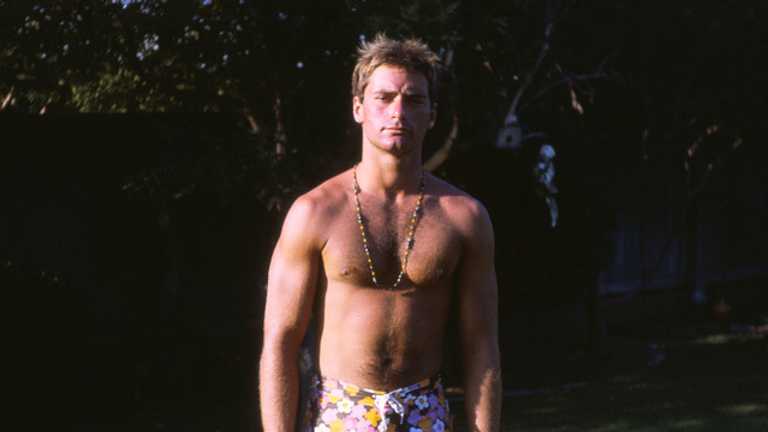

There is a good chance that somewhere deep inside an ancient metal filing cabinet, in a plastic file tucked inside a M*A*S*H-age Pendaflex hang folder, is a 35mm color transparency of Florida surfer Steve “Beaver” Massfeller taken by Orange County photographer Mike Moir. Both men were incredibly good at what they did. Both were at the height of their powers in the late ’70s and early ’80s. Sadly, both men died last week, Massfeller, a week ago today, at age 68; Moir on Monday, age 77. No information at this time on how either died.

Massfeller is best known as the surfer who came nearest to dying while competing in a WCT event. In 1983 he went head-first into the reef during the Pipeline Masters prelims and minutes later was pulled from the water without a pulse. He was air-lifted off the beach, survived, had surgery after surgery, first in Hawaii then in Florida—one of them to fit a plate above his now-sightless right eye where the damaged skull had been removed just after the accident—followed by months of rehab, and eventually returned to surfing and competitive paddleboarding. For inspirational long-odds true-grit comeback stories, you’ve got Bethany Hamilton and Beaver Massfeller and somebody else, take your pick, way back there in third.

But in Beaver’s case, the comeback story, great as it is, obscures all the accomplishments he made in the years prior to the accident. He was the best Florida-born big-wave surfer of his generation, or any generation prior, for that matter, and maybe a generation or two following. Slater winning the Eddie, the Hobgoods and Cory Lopez charging Pipe and Teahupoo—that’s how far you have to go into the future to find East Coast surfers who were on Massfeller’s level in terms of courage and commitment, and Steve did it the old-fashioned way, buying a one-way ticket to Hawaii right after high school graduation and parking it on the North Shore, where he lived for nearly 10 low-budget high-hope years. Beaver surfed everything, anything, small and clean, huge and windy, didn’t matter, just put the time in and climb the ladder. A high point came In 1978, when Massfeller and fellow Floridian Pat Mulhern, in solid 8- to 10-foot waves at Sunset, won the World Team Challenge, beating Peter Townend and Cheyne Horan in the finals.

Finally, behind those two things—a headline-making accident and a decade of big-wave gnarliness—is the actual person, Massfeller in the flesh, and while reading various posts and comments on Steve over the past few days, the one that sticks with me (and I suppose this has everything to do with my own state of mind, given the surf-world death toll and the general pan-global grimness of the past few weeks) is this Animal House-adjacent scene offered by Massfeller’s longtime friend Greg Hall:

Steve Massfeller was my housemate for a year or two at Sunset Beach. We lived in an old four-bedroom plantation house just off Kam Highway. It was country living. I had a veggie garden out back. The house was filled with surfing transplants, transients, and hopefuls, some whom went to fame and fortune. It had a big living room, the walls all covered with cut-out surf magazine pictures stapled up to look like wallpaper, a large crunched-in old couch, a couple of chairs on either side of a coffee table, and a tiny AM radio. No TV yet on that side of the island. Our only home entertainment was Radio Mystery Theater, a crackly CBS-broadcast show that made it to us from Kauai. Well, that isn’t entirely true, because dominating the space was a ping-pong table. We held skateboard races around the table—a Grand Prix of sorts!

We’ll leave Steve Massfeller there, racing around a beatdown North Shore ping-pong table with a gang of blow-in surf pals, shouts and curses and manic laughter filtered into into the kettledrumming churn of a new northwest swell.

I didn’t know Mike Moir especially well, but we hit it off right away in 1985, when he was a senior SURFER staff photographer embedded with all the hot young guns at Newport and Huntington (Moir was to Echo Beach what Craig Stecyk was to Dogtown: he created the scene as much as he chronicled it) and I was the magazine’s gee-whiz Jimmy Olsen newbie associate editor. We stayed in touch through the years, email and the occasional phone call, and my guess is Mike never Grand Prixed around the rec-room furniture with a group of screaming friends—LeRoy Grannis excepted, Mike was the most dignified and deliberate person in the game.

Two things. First, Moir had real physical presence. Big arms, broad chest, hard stare, and a voice befitting his size, deep and resonant and reserved. At one point in his life, Mike had been a full-on door-knocking Jehovah’s Witness, but put him in a Rams uniform and he could have replaced Merlin Olson in the Fearsome Foursome.

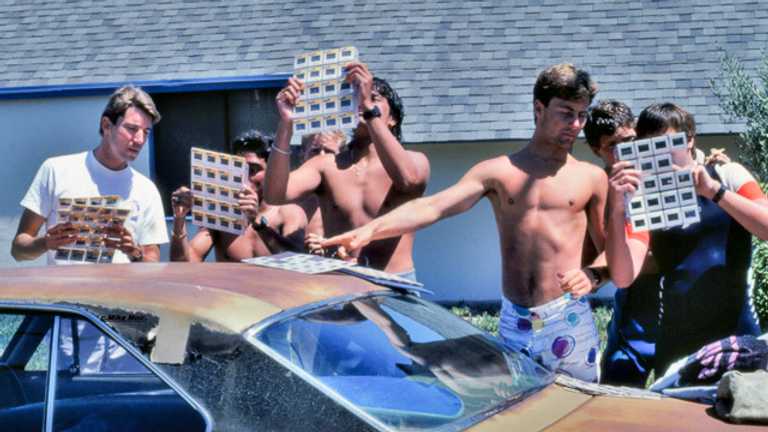

Second, Mike was born and raised in Canada and joined the US National Guard as a young man, and I’m stereotyping here but both of those pre-surf-career experiences seemed to define him—Moir was polite and tough, organized and dependable, very much the opposite of the noisy and mostly flakey Orange County surfers who by the late 1970s were creating the new high-performance post-black-wetsuit age of California surfing and gathering like tiger moths before the arrayed OC-centered telephoto lenses belonging to Moir, Larry “Flame” Moore, Peter Brouillet, and Chuck Schmid. Flame would become the most famous of the group during the sport’s coming Second Boom. But Moir, to my eye, was the best all-arounder and closest to the all-bases-covered color-saturated gold standard set by Ron Stoner.

But where Stoner invented and played up the surf-photog-as-media-star character—the camera-slingers of the ’70s and ’80s had a position and cache within the sport that today’s generation cannot even imagine—Moir did everything but wear an invisibility cloak to remain behind the scenes. It wouldn’t be wrong, exactly, to say he was humble. But Mike very much knew what he was about, and where he stood talent-wise. I was reminded of this fact just yesterday, while looking at Moir’s 1987 SURFER portfolio article. I wrote the intro for that piece, and asked Mike to come up with a headshot to go with it. A week or so later he reluctantly handed over a semi-abstract color slide of a wooden parking lot wall with a metal barrier running horizontally across the bottom of the frame. All we see of Mike is a blurry-edged silhouette, against the wall, holding a camera to his face. “A self-portrait,” Mike wrote in the caption. “I value my anonymity. It gets me in to shoot places where otherwise I might get hassled.”

What I didn’t notice until yesterday is that the metal barrier, just to Mike’s left, has a short all-caps piece of graffiti. Just one word: “KING.”

Mike was sly like that. He never tried to stand out and was always better than you remembered.

Thanks for reading, and see you next week.

Matt

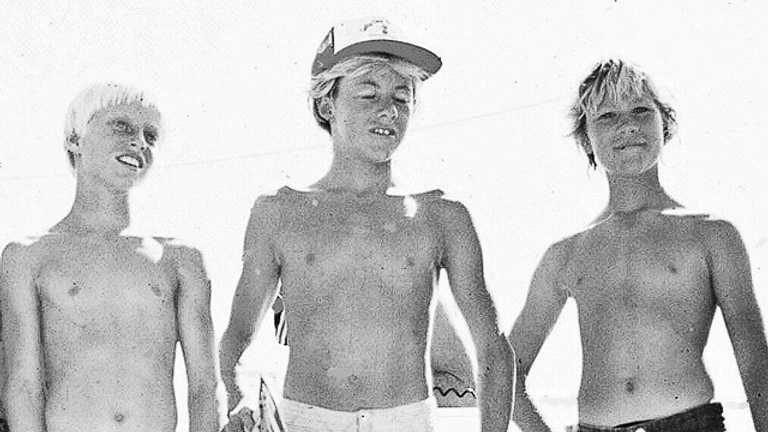

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: Mike Moir 1987 self portrait; Newport surfers, around 1980, photo Moir; Steve Massfeller, 1979, photo by Larry Pierce; the LA Rams’ Fearsome Foursome, around 1965; Richie Collins, late ’80s, photo Moir; Steve Massfeller in Florida. Color shot of Massfeller at Waimea by Gordinho. BW shot of Massfeller at Waimea by Sato. Photo of Mike Moir, taken around 1967, by his mother. Danny Kwock on the 56th Street jetty. Huntington crowd. 1981 trophy presentation with David Eggers, Doug Silva, and Jeff Booth. Mike Estrada cutback at Newport. Newport crew looking at slides. All photos by Mike Moir.]