SUNDAY JOINT, 12-29-2024: TARZAN SMITH, THE FIGHT OF A LIFETIME

Hey All,

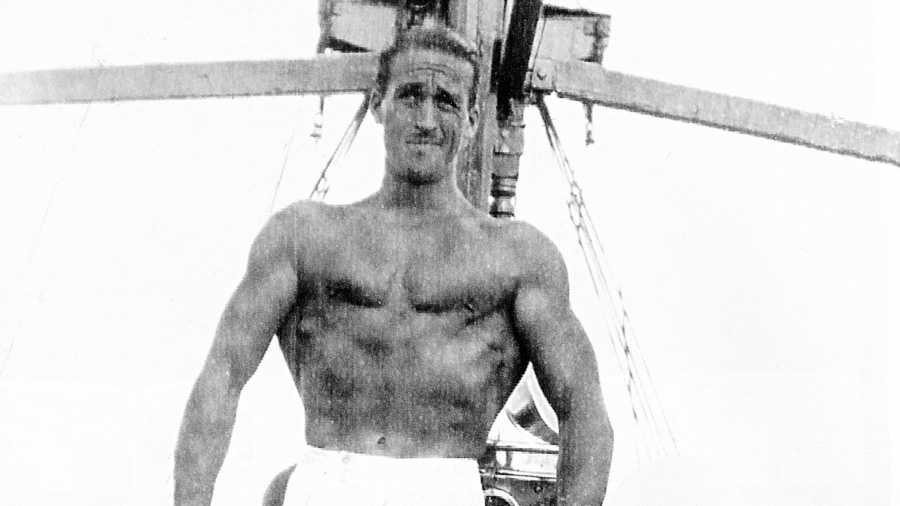

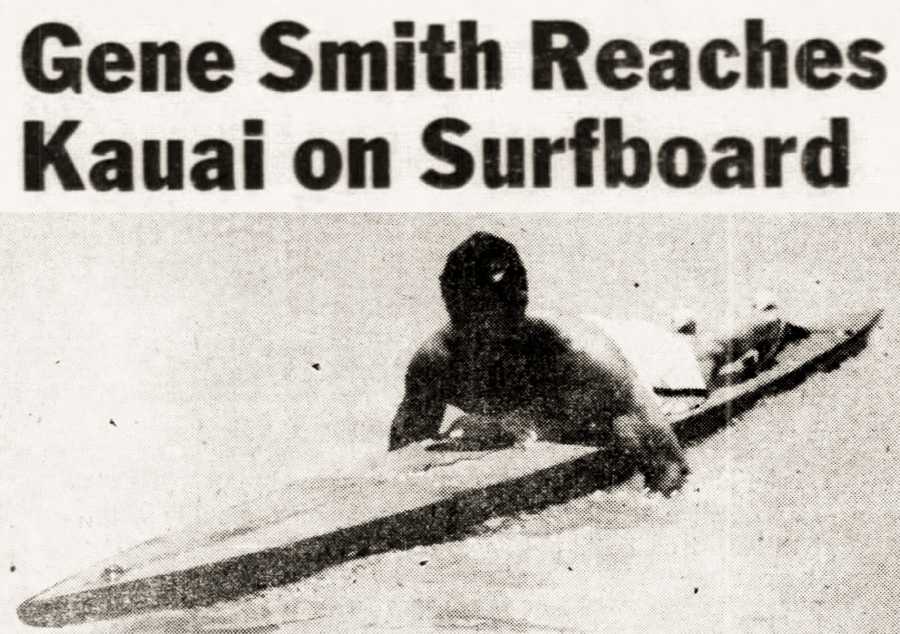

Gene "Tarzan" Smith spent most of the Depression either in Hawaii or Southern California, surfing and lifeguarding. He was superhuman on a paddleboard, and in 1940 became the first to cross the 90-mile channel between Oahu and Kauai. But to those who knew him personally, friend and foe alike, Smith was best remembered as a bull-sized, bloody-knuckled, never-say-die street fighter. Surf historian Malcolm Gault-Williams has written extensively about Smith, including a 1998 feature article in Surfer's Journal. Gault-Williams clearly holds Smith in high regard, and dwells at length on his subject's many ocean-going feats. But violent episodes are stamped up and down the Gene Smith timeline, and Gault-Williams, to his credit, doesn't look away.

If you read Gault-Williams' article casually, and squint your eyes a bit, Smith comes off as a wave-riding Marv from Sin City—brutal to the extreme, sure, but warped and loopy and funny in a flying-anvil kind of way. Here's Tommy Zahn telling Gault-Williams about Smith's days as an Orange County lifeguard and party boy in the mid-'30s. "Gene was living in a cave at Corona Del Mar, with his dog. He had one suit of clothes and one pair of shoes. On Saturday nights, the big kick was to go to the Rendezvous Ballroom in Newport. So Gene would get out his paddleboard, with his suit on, tie and shoes draped around his neck, roll up his sleeves and pant legs, paddle across the channel, and walk up to the Rendezvous. He loved to drink, and was never happy unless he got into a big fight. He'd usually take on two or three guys. At the end of the night, totally thrashed-out, he'd jump on his board, paddle back across the channel, suit and all. Monday morning, he'd take the suit to the cleaners."

What a kicker that last sentence is. You can almost see the big man there at the local A-1 Chinese Laundry, in full Gene mode, no more Tarzan, quiet and polite, strips of plaster on his face as he carefully points out the blood spots, tucks a claim ticket into his chinos, and says he'll be back on Wednesday.

But dig a little deeper and the Tarzan Smith story is predictably, infinitely sad and messed-up. Mother died young, violent father, foster care, lots of moving around, reform school. Then at the start of the Depression, when Smith was 19 and just off a two-year stint as an Oregon lumberjack, he arrived in the Laguna-Balboa area and started surfing.

You'd be stretching the facts to claim that surfing and paddling saved Gene Smith. Both his marriages were short. No kids. Never really settled down, and never more than a few weeks away from another violent episode. Then again, it's safe to say that Smith was less broken for his years spent in and near the ocean. If there was solace in his life, it was found riding waves or paddling for hours at a time, or in the company of Tom Blake, Tommy Zahn, Mary Ann Hawkins, and a few other beach acquaintances. Had Smith gone east from Oregon after his lumberjacking period, instead of down the coast to Southern California, it's easy to imagine him in prison or dead before 25. Instead he became, as one Honolulu newspaper put it, an "all-around surfing champion" and "Hawaii's peer of surfboard riders."

I'm always on guard against overstating the benefits of surfing, just as I'm always ready to point out that a dedicated surf life is itself filled with pitfalls and dead ends. But I do think that you can prove surfing's worth, or at least measure its remove from the larger world of sports and recreation, in the way it welcomes the broken among us and gives them time and space, a mindless healthy task, a beautiful view, solitude or alliance, as needed. Smith got all that.

On the other hand, with Gene Smith you probably want to leave off in the mid-1940s, not too long after his epic Oahu–Kauai paddle. Otherwise you end up in a Honolulu alley in 1947, with Smith left for dead after getting jumped by four policemen. Smith, at the time, was a cop himself. Or 1976, with Smith, age 65, sprawled atop a pile of cardboard boxes behind a Santa Monica Safeway store, handcuffed with a broken leg, the work of three store guards. Or 1986, with Smith dying alone in Brawley, California, a flyspeck desert town 120 miles off the coast.

Surfing heals, and that is wondrous, almost miraculous.

Surfing heals, but it does not save. Not Tom Blake. Not Miki Dora or Michael Peterson. For sure not Gene Smith.

* * *

I originally posted this in 2017, and wanted nothing more to do with Tarzan Smith. I'm not especially put off by accounts of surf-adjacent violence, but I'm inclined these days to steer clear of it, even in storytelling—plus I have almost zero interest in paddleboarding and I know that means I'll never get my waterman epaulettes, but so be it. However, last week I reread Dorian Paskowitz' darkly comic and fantastically detailed account of the time he was dragooned into being Tarzan's backup in a Waikiki Tavern showdown with a group of Primo-soaked beachboys. It is always a joy to come back to Dorian's writing, and his sane-man-navigating-a-sometimes-insane-sport yarns. Paskowitz himself, of course, was in many ways as oversized a character as the people he wrote about—and maybe not as sane as he appears in his prose—but nobody else puts me as close to myself, in terms of how to manage the people and vagaries of surfing, as Dorian. His tale, in any event, got me back into Tarzan's world and here we are.

More prosaically, revisiting Gene Smith provides us with another reminder that history is a greased pig of a vocation, and while I come off in these posts like I know my business at any given moment, on any given topic, the older I get the less surprised I am to see my historical tee shots hook into the weeds of error or fable, instead of landing on the greens of accuracy and truth.

This account of Tarzan's 1940 Oahu-Kauai paddle, for example, written in 1944, is the one I've always relied on, and we are thrilled by "the sound of a shark splashing," and Smith paddling bravely on despite being "covered head to toe" with man-of-war stings, and an encounter with a "sea monster" (manta ray, actually), which required four bullets to kill. But in the original story, which appeared on the front page of the Star-Bulletin the day after the actual event, is much lower key—Smith tells the reporter he hit some choppy water midway across the channel, but otherwise "the trip was uneventful."

Manta rays, by the way, are big, gentle, stinger-free, plankton-eating creatures with dolphin-like intelligence, and seem to like nothing better than doing slow friendly laps around swimmers and divers.

Thanks for reading and see you next week!

Matt

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: Honolulu Police badge; Gene Smith and tandem partner at Corona Del Mar; Smith as a Honolulu policeman, around 1945; Smith after one of his interisland paddles; manta ray engraving; dancefloor action at the Rendezvous Ballroom, 1938. Smith and his second wife. Smith, center-right, with fellow paddlers, in 1940. Smith on a steamer, heading to Hawaii. 1940 newspaper headline]