SUNDAY JOINT, 2-2-2025: HOW TO LOVE ANDY WARHOL'S SURF MOVIE WITHOUT ACTUALLY SEEING IT

Hey All,

Andy Warhol and a handful of his brightest Superstars arrived in San Diego in May 1968 to make a film with the working title of "the surfing movie." It was a surfing movie the same way Lonesome Cowboys, Warhol's previous film, was a Western—basically not at all. But the film was indeed set front and center in the surf world. Warhol's crew rented a house at the south end of La Jolla's Marine Street Beach. Andy himself walked into local shaper Carl Ekstrom's shop and bought a pair of new boards off the rack. The surfing movie had an outline of sorts—unhappy bourgeois married couple rents their home to a bunch of surfers, and while husband and wife both make eyes at the young hunks, only one (no spoilers!) will receive the Warholian surfer-boy golden shower—but no script, no plot, and just the barest direction. Improv was the standing order.

The shoot took three weeks, blew through hundreds of hours of 16mm film, and everyone flew back to New York with a sunburn.

Less than a week later, a schizophrenic Warhol Factory hanger-on named Valerie Solanas, upset that Andy had not produced her filicidal single-act play Up Your Ass, walked into his studio with a .32 Beretta, put one bullet in Warhol's chest, another in his abdomen, and walked out unnoticed. Warhol survived, but barely. While he'd be an active art world fixture for years to come, he never got his mojo back artistically and died at 58 in part from lingering effects of the shooting.

The surfing movie, in any event, was shelved until 1995, when the Warhol Foundation hired Andy's second cameraman (and part-time rival) Paul Morrissey to do a final edit, and in 2012 the now-named San Diego Surf premiered at the New York Museum of Modern Art as a meandering 90-minute hot screwball-cum-satire ambisexual mess. There were a few one-off screenings here and there, but that was it, San Diego Surf went back into the vault.

A SURFER Magazine reviewer attended one of the shows in 2012, and their thumbs-down review ended by saying the "best-case scenario is that San Diego Surf will bore you to tears." My kneejerk instinct here is to call out the Bible of the Sport for being S-Q-U-A-R-E but the magazine has been moldering in the print-media graveyard for five years so why bother.

But also, let's be fair, maybe SURFER was right.

I liked Andy Warhol's art before I knew who Warhol even was. This is not me being precocious or cool or anything like that. The appreciation was just there for the taking. All those giant Campbell's Soup cans and heavy-lidded Marilyn Monroe fluoro silkscreens turned millions of Boomer kids into Pop Art fans without us even knowing it.

So I was predisposed to like Warhol's paintings, in other words. His movies, on the other hand, from what I've seen (not much) and read, are as hard to like as his Kennedy-era canvases are easy. My take on Warhol's hundreds of films is the common one: nobody is much trying in those movies—least of all Warhol himself.

Three years ago, Ben Marcus wrote a BeachGrit piece on San Diego Surf, which can only be seen (the movie, not the article) by visiting the Warhol Library in Pittsburgh. A few culture-curious surfers have made the trip, and Ben called some of them find out what the film was like. One of them described San Diego Surf as "fascinating and boring at the same time," which sounds right.

Marcus reached out to another person who'd seen San Diego Surf, asked if it was a "homoerotic surf movie," and was told it was a "surf-erotic homo movie." This glib little piece of gay-bashing—which I read for the first time this week, which in turn sparked this Joint—made me want to be a Warhol film fan in spite of myself. Turns out I'm not alone. Reid Rosefelt, a longtime NYC-based writer and film publicist who has worked with Jim Jarmusch and Pedro Almodóvar, among others, said in 2012 that he was a "huge fan of Warhol’s films, despite the fact that I had never seen a single one." Rosefelt went on to describe the one and only conversation he ever had with Warhol, which happened in the late '70s.

“Excuse me, Mr. Warhol, may I ask you a question?”

Warhol looked at me with his trademark languid affectlessness—a pose or really him?—the ultimate in coolness. He didn’t say anything.

“I’ve read all about your films, but I can’t see them.”

“Oh…” he said.

“Are they in distribution somewhere? Do you have any plans to bring them out?"

“Not really.”

“You really should. A lot of people want to see them and they can’t.”

“Isn’t it better that way?”

So here is my bit of improv for the week. I suddenly very much appreciate that Andy Warhol made "a surfing movie," however you want to define the phrase, even if all I really want to see is maybe a 10-minute cut of San Diego Surf, not the full 90-minute feature. It is enough to know that San Diego Surf is funny, for starters. Watch the trailer: the part near the end where the husband is doing the afternoon surf check while trying to impress the young stud he's sitting next to, faking like he's a hot surfer, saying in a blasé voice that the waves are not inspiring him "'cause it's not big enough." No disrespect to my own tribe, but that bit is funnier than anything Paul Witzig or John Severson or MacGillivray-Freeman did in 1968. Whether or not you think San Diego Surf is (or was) transgressive is down to where you happen to draw those boundaries. But there is no denying the film has the confidence to go silly, and that alone is a mark in Warhol's favor given that surfing at the time was knee-deep in its own imitative counterculture pretentiousness.

Finally, and this is probably the wellspring for every good feeling I have about San Diego Surf, the people involved with the project all seem to be having a good time. Nobody is in La Jolla to tear the scene down or (as we used to say) "do a number" on surfers. Night-creeping New Yorkers like the beach, too, it turns out.

And for that reason, the San Diego Surf satire, for me, goes down easy. Rob Reiner's Spinal Tap works because Reiner and the cast are learned, deep-down, hardcore rock fans. Warhol and his crew don't know surfing the way Reiner knows music, but they're coming at it from the opposite direction of what Tom Wolfe did two years earlier (and less than a half-mile to the south, at Windansea), with his snark-first Pump House Gang essay.

San Diego Surf cast member Louis Waldon said, during the shoot, that he was, "interested in finding a new way to live, and surfing could possibly be the answer."

Warhol himself wrote that “La Jolla was one of the most beautiful places I’d ever seen," and that "everybody was so happy [there] that the New York problems we usually made our movies about went away [and] the edge came right off." Warhol did not live to see San Diego Surf screened for an audience, but he remembered the film as "more of a memento of a bunch of friends taking a vacation together than a movie.”

Thanks for reading, and see you next week.

Matt

PS: Chelsea Girls, maybe Warhol's best-known film—same thing as San Diego Surf: Looks great in this five-minute short, and I will blithely and with almost no foreknowledge say it is valuable and important, but no way am I sitting through a full three-and-a-half hour Chelsea Girls screening.

PPS: Take a look at young Carl Ekstrom, who today is very much alive and well at 81, and see if you don't agree that he could have been Warhol's first and greatest West Coast Superstar.

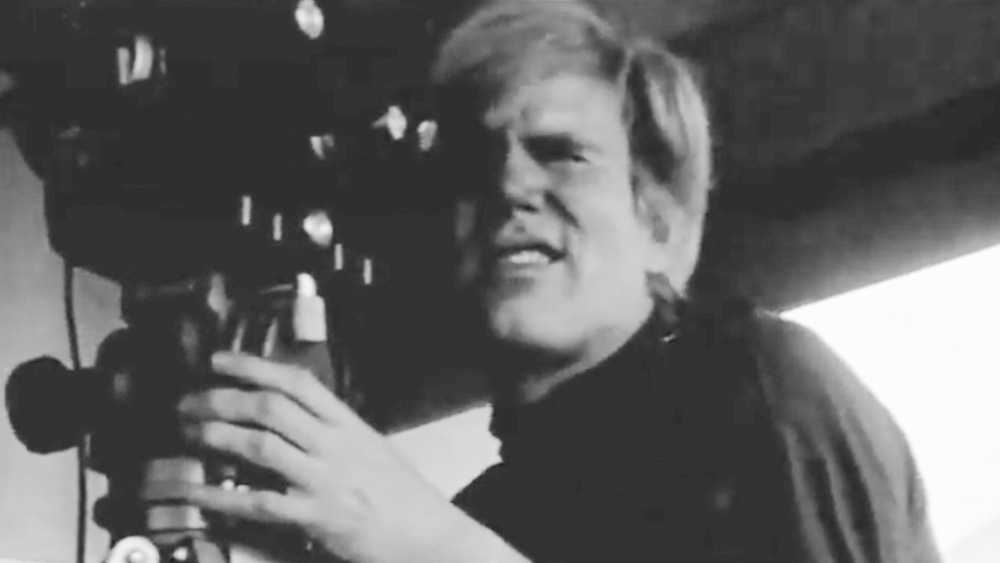

PPPS: Almost forgot. Andy Makes a Movie is a meandering 22-minute dirge of a documentary about the San Diego Surf shoot, but worth watching anyway for the behind-the-scenes images of Warhol at work. That white-trimmed beachfront house with the massive floor-to-ceiling windows belonged to Oscar-winning actor Cliff Robertson, best known to surf fans as Kahuna, the cool but borderline creepy shack-living guru from Gidget. Robertson bought the house in 1963, nicknamed it Casa de la Paz (House of Peace) and kept it until 2005, by which time San Diego had declared it a landmark. The renovation that followed, however, gutted everything but the facade. It had been Moorish to begin with but Robertson had his own ideas. As the renovating designer later said, “Cliff must have enjoyed getting high and going to Mexico to pick up funky tiles and just slotting them all throughout the house in a haphazard way." But as Kahuna famously put it, "Art is what you can get away with."

Just kidding, Warhol said that.

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick, 1965; vintage La Jolla postcard; Warhol filming San Diego Surf; Mike Diffenderfer surfing in La Jolla in 1969, photo by Glenn Fye; Warhol on the cover of Esquire, 1969; surfers in San Diego Surf. Three frame-grabs from San Diego Surf. Warhol on location in La Jolla. Beach scene at La Jolla in the early 1970s.]