SUNDAY JOINT, 8-14-2022: DALE DAVIS, SURF-KING OF TINSELTOWN

Hey All,

The surfer who came out on the wrong end of a nighttime death battle with the big rubber fish-man in Beach Girls and the Monster, as teased in last week’s Sunday Joint?

Dale Davis. Surfing’s own Mr. Hollywood—for better and worse.

Mostly forgotten today but a genuine surf-world mover and shaker in the 1960s, Dale was a cheerful well-tanned Rolex-wearing man on the make who produced movies, hosted a TV show, and lived fast and glamorous until he leaned a bit too far out of a helicopter while shooting Waimea Bay—but we’ll come back to that a minute.

There’s not much available background information on Dale Davis. I’m not 100% sure, for example, that he was born in 1940, as listed on his EOS page. Dale said he grew up in Hollywood, although it may have actually been Sherman Oaks, which is (ahem) pure Valley and zero Hollywood. But in 1962 Davis’ parents built a stunning four-bedroom home on Blue Jay Way, which is as Hollywood as it gets, just down the block from where George Harrison would later write “Blue Jay Way,” and for years to come Dale’s business ventures would use his parents’ address. Fake it to make it, and I’m not smirking, that’s how it’s done in LA, or anywhere else for that matter.

Walk on the Wet Side, Davis’ 1963 debut surf film, came out just after he graduated from the Brooks Institute of Photography, in Montecito. Wet Side is not great but not bad either, a highlight being a lengthy sequence of teenaged Midget Farrelly at Rincon, back when Midget was mostly unknown to us Yanks. Three more movies followed as Dale got into the one-film-a-year routine, while also hosting a 30-minute local TV show called Surf City, and making a never-sold TV pilot for teen idols Jan and Dean.

Things peaked in 1966. Davis was chosen to be featured in a semi-experimental documentary called Mondo Hollywood, and the sequence, narrated by Davis himself, shows him skateboarding down Blue Jay Way, heading to a poolside frolic with friends. The phone rings. A sunbathing starlet picks up, listens, waves Dale over. From the other side of the pool, he hops on a floating surfboard, glides to the shallow end, steps off and takes the call. The surf is up at Malibu! Next thing we see is Dale gunning down the driveway in a brand-new Mustang convertible, starlet in the front, board sticking out the back. Watch here. In its own way, Dale’s Mondo Hollywood showcase is a surfing fantasy every bit as dreamy (and embellished) as the Cape St. Francis chapter in Endless Summer.

Davis by that time was well into production for The Golden Breed, his fourth and best full-length movie, and for 18 months or so he could not put a foot wrong. Dale was there at Ocean Beach when Nat Young won the ’66 World Championships. He didn’t just shoot Miki Dora and Johnny Fain banging rails at Malibu, he got the two to go skiing together at nearby Big Bear where the Tom and Jerry routine continues. He shot Joey Cabell at Honolua, David Nuuhiwa at Pipeline, Billy Hamilton at Pupukea. Everybody in Dale’s movie looks upbeat, but nobody is happier than the filmmaker, who is not shy about giving himself screen time—and dressing the part. For a skydiving sequence, Dale wears a sharp red cardigan and smokes a pipe; while interviewing Fred Hemmings he shows off a thick gold ring to match his Rolex. The smile never stops, and it is not fake, it is not Hollywood, the guy is just having a blast.

The Golden Breed reviews in the mainstream press were mostly positive, which is remarkable considering that Endless Summer was still fresh on everybody’s mind. “While Golden Breed lacks the free-flowing style that made Summer such a great adventure,” the Los Angeles Evening Citizen wrote, “the photography is artistically equal, if not superior, to that of its award-winning counterpart.” (Davis took those reviews and went nuclear in his promo. “Brilliant in its execution!” was one of the headers for his next Golden Breed handbill, the other being, “Magnificent in its thunderous achievement!”)

Behind the scenes, though, things were falling apart. The lively first reel of Dale Davis’ life had already ended—and the second reel was leaning hard noir.

While in Hawaii, late in the Golden Breed shoot, probably December ’66 or January ’67, Davis went up in a helicopter to film Waimea. I’m guessing he shot a single roll, maybe two—you see the footage here and there throughout Golden Breed—but at some point, for some reason, he fell out of the helicopter and broke his back. Again, there is no hard information. Everybody knew about it but nobody actually saw it happen. The story didn’t make the papers. The only mention I can find in print is from a 1973 issue of SURFER, where Steve Pezman notes that “Dale was out of the game for four or five years recovering from a paralyzing fall out of a helicopter, landing on a surfboard at Waimea Bay.”

Somehow Dale managed to edit Golden Breed while recovering, but it took some time, and Breed didn’t come out until 1968, at which point it might as well have been Sir John Gielgud reading excerpts from Canterbury Tales; the surf world was mid-revolution and Wayne Lynch was here to carve figure-eights around Greg Noll and most of the rest of the Golden Breed stars. The film bombed. Liquid Space, his 1973 comeback film, also went nowhere, and unless I’ve missed something, that was it for Dale’s surfing career.

Nathan Myers helped research the print version of Encyclopedia of Surfing, which was written in the early 2000s. Nathan didn’t talk to Dale himself, but did get in touch with some of his friends, as well as his sister. Dale had a website at the time, where he sold VHS copies of his old surf movies along with, as Nathan phrased it, “very soft” skin flicks, which Dale shot himself. “2001 was a bad year for Dale,” Nathan said in his notes. “[He] was shot in a drive-by while walking his dog in LA. When I first spoke to his sister, he was in the hospital for a stroke. Next thing I knew, he was dead of one.”

Four years ago, Dale’s sister left a comment on a YouTube video which reads, in part:

Dale was my older brother. His earlier years were charmed. He lived to surf, skateboard, anything with a board, on the street or in the water. Unfortunately he couldn’t keep up with the big buck guys after Endless Summer. His TV show in the early 60s was kitschy to say the least. He always lived life on an edge and became a victim to it. He passed away September 13 at 12:01 AM. He is buried in Los Angeles under a tree. His stone says, “He caught the last wave and rode it home.”

Thanks, everybody, and see you next week.

Matt

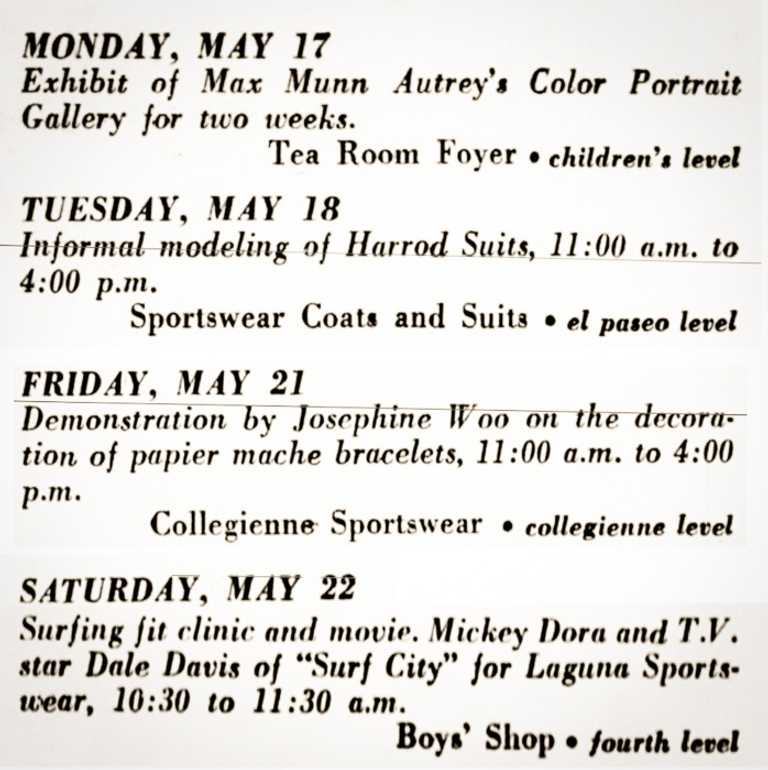

PS: Detail from a May 17, 1965, Los Angeles Times ad for Bullocks Department Store, San Fernando Valley. Ad headline: “Schedule of Events for Wonderful California Week.”

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: Midget Farrelly in "Walk on the Wet Side;" Dale Davis; helicopter; Hollywood Hills; detail from Golden Breed handbill; Davis interviewing Jeff Hakman in Golden Breed. Midget Farrelly at Rincon, and on the beach. Dale Davis and pilot; Davis and Fred Hemmings; Davis and Jackie Eberle; all photos from Golden Breed. Detail from Liquid Space poster]