"FORTUNATE SON: THE UNREAL WORLD OF CHRISTIAN FLETCHER," MATT WARSHAW, 1990

Matt Warshaw's profile on Christian Fletcher ran in the April 1990 issue of SURFER. This version has been slightly edited.

* * *

What’s important to you?

Having fun. Having fun every day. Those guys on the World Tour don’t have fun. I know that for a fact. I did it in ’87—it was hell. You spend 60 hours traveling from one place to another, live out of a duffel bag and never get to eat home-cooked food. The guys on Tour, they worry too much. They’re always worried.

How is your life different?

Me, I do whatever I want. Every day. No school. No job. All I do is surf, skate, travel and have fun.

* * *

If good fortune is a finite element on this planet, like carbon or helium, then somewhere out there is one broke, ugly, clumsy wretch of a surfer, living only to counterbalance the unbelievable amount of luck laid on Christian Fletcher.

Can anyone relate, really relate, to this kid’s life? Does anyone in the surfing world have it better?

First, he's a counterculture hero for staying away from a formatted life on the world championship tour. As a 90% anti-contest surfer, Fletcher gets paid a good (undisclosed) salary to travel and surf where he wants, when he wants, responsible only to turn up for the occasional photo shoot. The image for sale is Hard Rock Aerial Soulman, and it's the hottest look going. Christian is a media sweetheart of the highest magnitude—at one point scoring the covers of both leading surf magazines in the same month.

Shifting gears, Fletcher recently proved he can beat his idealistic enemies at their own game. His $31,725 win in the Body Glove Surf Bout last summer was a walk in the park.

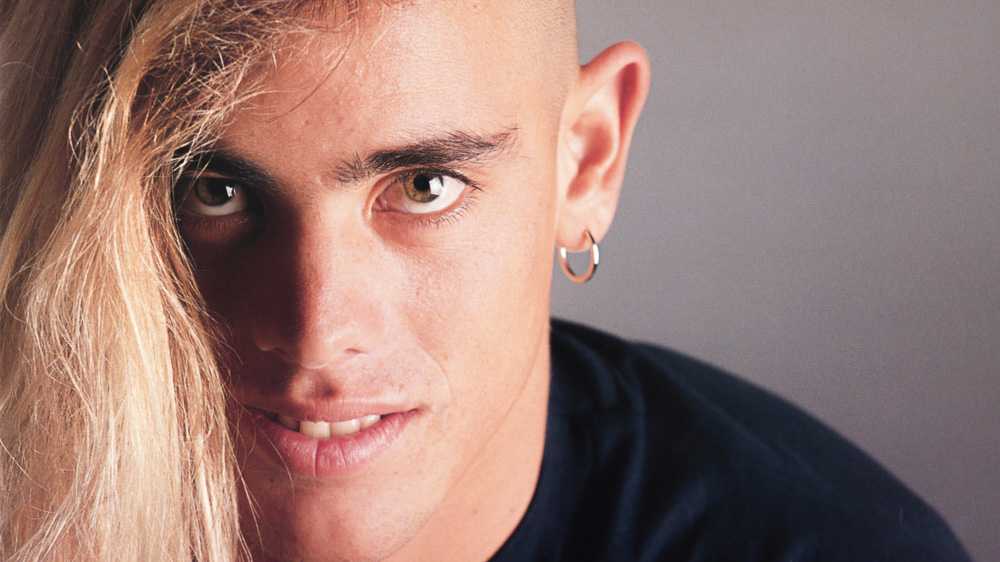

Christian Fletcher, 19, has grown up good-looking and talented, in the bosom of the world's great surf families. It's been an absolutely unique existence.

Do you vote?

No.

Do you have any heroes?

Not really. I don’t think you should put other people above yourself.

How do you relate to Born-Again Christians in surfing?

They don’t bother me as long as they don’t preach. I don’t digit when people preach—no matter what it’s about. I don’t want some guy telling me what’s good in a stereo, and I don’t want some guy telling me about the Bible, either.

Do you enjoy being a famous surfer?

Not really. If I had my way I’d rather be left alone. (Pause) But being famous, that’s the way I make money. And I don’t feel like getting a job.

Any regrets in life?

I took guitar lessons when I was a little kid, and I should have stayed with it. But the guy wanted to teach me "Mary Had a Little Lamb", and stuff like that. My brother Nathan, right from the start, was learning Metallica.

Any guiding philosophies you live your life by?

(Pause) This was what I was told growing up: Don’t lie, cheat, steal or play ball in the house.

* * *

Christian Li Fletcher was born October 20, 1970, at Kahuku Hospital on Oahu. While the family heritage was good, family finances were low: Father Herbie was in a pre-Astro-Deck money slump, working for Clark Foam Hawaii. Mother Dibbie was a housewife. The Fletchers lived on the North Shore until 1972, moved to Sun Valley, Idaho, for two years, then to Beach Road in Capistrano Beach in '74—back when a small, lower-middle-class surf family had a shot at an affordable beachfront rental; four-or-five years before the Orange County real estate market went berserk. The Fletchers have been in South Orange County ever since.

As mentioned, the family tree is loaded with surf-world notables: Herbie was a finalist in the 1966 World Titles and an early backside ace at Pipeline, and now stands as (arguably) the world's best 41 -year-old surfer.

Grandfather Walter Hoffman and great-uncle Flippy Hoffman were pig-iron for the modern hellman, and among the first to surf Sunset Beach in the early '50s. The Hoffman brothers are now leathery, gruff and sage— and wealthy, thanks to Hoffman Fabrics, the family business. Aunt Joyce is a two-time World Champion and four-time SURFER Poll winner.

Cousin Marty is keeper of the Hoffman brothers' flame: surf-adventurer, big-wave purist and businessman, crusty at age 28.

And Nathan Fletcher, Christian’s beefy 14-year-old brother, already has 11 years' surfing experience and may be the most talented of the bunch. In five years’ time he could eclipse Christian's accomplishments.

Herbie built Christian a surfboard when the boy was one, so he doesn't remember learning how to surf. His earliest surfing memories are of Doheny, when he was four. At age five, entering his first contest, Fletcher won the 8-and-Under division of the San Onofre Surf Club contest, and went on to win his division of the Sano event nine-out-of-10 years.

On the whole, however, competitive achievement has been scarce. Fletcher finished second to David Eggers in the Boys' Division of the 1982 U.S. Championships, and three years later was third in the NSSA Open Season, but he can’t come up with much else. He turned pro in late 1985, and spent the last four years either in a state of competitive struggle or indifference. His noteworthy result prior to his jackpot win at Trestles came in summer of '88, with a win in the juniors division of the San Clemente Longboard Classic, good for $2,000.

Fletcher's win in the Body Glove Surf Bout—held in good 2-4' peaks—was decisive and clear. Still, fallout may prove harmful. Because $30,000+ in prizemoney is a screaming big amount for our provincial little sport, Fletcher was given the collective attention of the surfing world. And because he’s been raised to speak his mind—and because he has the subtlety of the average teenager coming onto his first power high—Fletcher's come out firing. The day after he won the Trestles contest, Fletcher called standard of PSAA surfing "weak.” A month later, when asked to amplify, he said, "Evybody surfs the same. Guys are just going rail-to-rail, over and over, butt-wiggling and riding all way to the beach. That's not way it should be. Surf the wave while it's worth surfing, then kick out." He’s quotable, if not intellectual, mixing hard truth with vacant, metalhead posing.

Fletcher, to say the least, is not introspective. If he contradicts himself, he just shrugs and moves on to the next subject, and big statements come with the simple, strong conviction of a man who’s never in his life been conversationally shot down. He is sweet by nature, but instinctively knows sweet isn't what 19-year-olds are all about.

How would you be dressing, acting, looking, if you weren't a famous surfer?

The same.

So the way you’ve been portrayed is the way you are?

Yeah.

Your image is rebellious. But from talking to you, and according to people who know you well, you’re really just a nice guy.

People who don’t know me think I’m a lot worse than I am.

Some of those people also wonder if your parents, or your sponsors, have created you.

I got pushed into having long hair by my Mom; she always wanted me to grow it. I used to get sick of it. Now I like it long.

But you don’t feel like you’re being manipulated?

No.

Because you’ve been getting so much press, there’s bound to be a Christian Fletcher backlash. Does that worry you?

As long as I keep going out there and doing what I’m doing, I don’t think anyone can really come down too hard on me. I don’t think people want to see boring, conservative surfing.

* * *

Fletcher’s been knocked hard lately by members of the ASP Top 30 as a lesser talent, a puppet for Herbie Fletcher and Astro Deck, and a shameless media whore. But Fletcher's uniqueness is a fact.

His surfing is experimental; sometimes bizarre. His personality is by turns quietly pleasant, sleepy, aloof, with none of the flat-affect pathos of Matt Archbold (who comes closest to Fletcher in surf style and alternative-career style), none of the anger of Sunny Garcia, and none of the weird determination of Richie Collins. He's even further removed from his East Coast counterparts, straight-arrows Todd Holland and Kelly Slater.

And he is the polar opposite of Jeff Booth, the WCT fundamentalist who has gone to literary pains—a rare gesture among pros—to distance the entire world tour roster from Fletcher's new form of professionalism.

(A sharp promoter out there could take a tip and set up a megabucks’ surf/lifestyle showdown: Booth vs Fletcher, man-on-man, in a one-hour heat at Lower Trestles next summer. Pick up $10,000 from Town and Country and $10,000 from Quiksilver, and you have the sideshow event of the year.)

It’s hard to say if Christian Fletcher chose his role as anti-contest rebel or had it forced on him after failing to make a dent in the WCT ratings after traveling to France, England, Spain, Japan, Brazil and Hawaii.

Some feel it’s hard to say if Fletcher even chose his role as anti-contest rebel at all—Herbie and Dibbie have had that strong a hand in his affairs. (Young Nathan has so far proven to be the independent thinker of the family. Earlier this year he announced to Dibbie that he was tired of hassling with long hair, and wanted it cut. Dibbie said it wasn’t a good idea; they'd worked a long time to build a certain look and image. The next day Nathan came home nearly bald, and handed Dibbie his hair in a shopping bag.)

Regardless of origin, Christian Fletcher’s position of independence within surfing is solid. He's so independent these days, in fact, that surfing itself has been put on hold. For the past four months, skateboarding has been the main thing in Fletcher's life—he’s been driving his battered Chevy Celebrity up to Hollywood to skate Christian Hosoi's 11' ramp, and it's been a revelation. “The only other time I get that kind of rush is surfing Pipeline. When you get a big wave there and make it, you're totally shaking with adrenaline. On a ramp, lately, I'll get six-or-seven airs in a row, and by the time I'm done it's the same thing—I'm just shaking.”

Risk is part of the reward. Fletcher knows he could land the wrong way, shatter a knee and a career at the same time—and the idea actually brings a smile. "Maybe that’s why it's such a rush.”

How important is style to good surfing?

I think guys used to concentrate more on style. Like the guys back in the seventies; Michael Peterson and Rabbit—I like the way they got in the tube at Kirra and Burleigh. And Barry Kanaiaupuni at Sunset; that’s style. Now it’s a lot of bright colors, a lot of hopping and a lot of arm-waving.

But you wear bright colors.

Yeah. (Pause) Well, that’s how you get shots. That’s how you get noticed. But as far as just surfing goes, I’d rather watch older guys. Guys wiggle over here and jam a move, then wiggle over there and jam a move. It doesn’t flow together. It’s all broken up. I try to go from move to move without doing a lot of little turns.

* * *

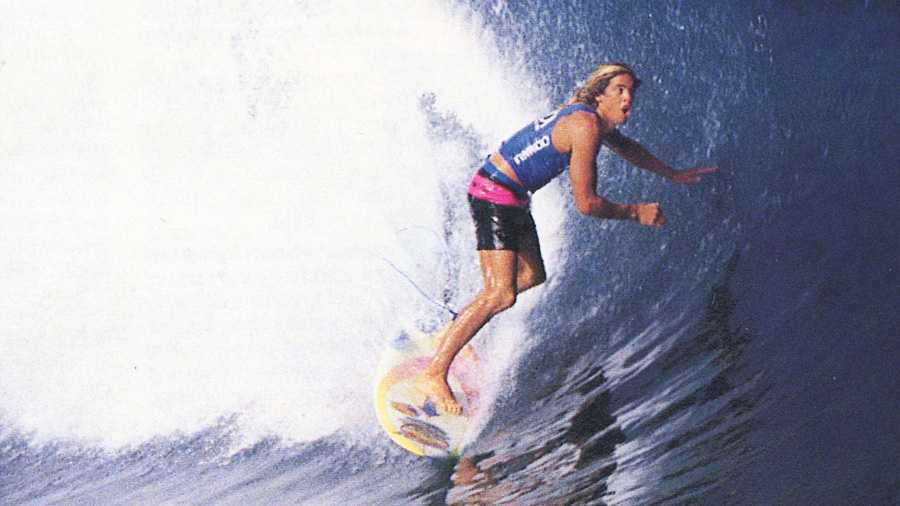

It's worth nothing that while Fletcher made his way through virtually all rounds of the Trestles' event on the strength of his aerials, he won the Final with clean, positional surfing. He did a single air, but it was inconsequential to his victory. Fletcher talks as much about flow and style as he does aerials. He speaks about the lack of power in most people’s surfing, but at 5' 10" and a slender 150 pounds, he's too lanky to put much torque into his moves. Eighteen years of surfing, however, have ensured that he gets from move to move with virtually no extra motion—and while Christian's act isn't nearly as aesthetically pleasing as the early '70s surfers he admires, its silk compared with them majority of his generation's pump-and-squat artists.

Some days, depending on conditions and conditions or Fletcher’ mood, he won’t attempt a single aerial, and can look either ultra-casual or disinterested.

Other days, when the mood hits, he's off and flying at evert opportunity. Nobody can touch Fletcher for height, innovation and variety in aerials—not Potter, not Archbold, not Slater. Watching him ride when he's feeling experimental is one of the great voyeuristic thrills in surfing.

* * *

What’s at the root of the problem with surfing today?

Money messed things up. Everyone has the contest style; to win contests, to make more money.

Will things get better?

The kids are going to get more radical—I see them doing it already—and the contest people need to understand that. So, yeah, I think things will have to change—and I’m going to be right there when it happens.

With all the genetic and environmental gifts bestowed upon Christian Fletcher, it might have been possible to forecast his development up to this point. But now things begin to get really interesting. Expectations and notoriety will weigh heavily on Fletcher from here forward, leaving room for either rapid progression or spectacular flame-out.

A lot of people are eager to see the inevitable dose of reality injected into Fletcher's world—and when it hits, it'll be interesting I to see what kind of reaction it sets off in his psyche, and his surfing.

But here's where Fletcher could I play an ace. The fact is, even surrounded by unreality and naïveté, he often sounds reasonably well-adjusted. On top of everything else, he may have been born with the ability to cope.

Time will tell.