SUNDAY JOINT, 11-10-2024: ALOHA AND THANK YOU PHYLLIS O'DONELL AND PAT MCGEE

Hey All,

Phyllis O'Donell, who won her final in the 1964 World Championships at Manly Beach about 45 minutes before Midget Farrelly won his, and thus became our sport's first world champion, died this week at age 87. She was private and level-headed, intense but funny, upbeat by nature. Zero pretense. Sure-footed in every sense of the word. O'Donell loved getting in the water, and for 15 or so years loved riding waves most of all, and clearly she was ambitious and goal-driven—but I can't think of anyone, at her level, who was less interested in surfing as a path to money or fame.

Back to the '64 championships. It was a mild late-autumn Sunday afternoon, with a huge crowd on the beach and along the seawall. Fun sandbar waves, mostly rights. Sydney-born O'Donell was the newly-crowned Australian national champion but she paddled out as a longshot underdog to Linda Benson of San Diego. Five years earlier, Benson, as a tiny high school sophomore, hot-dogged her way to victory in the Makaha International, was then featured in movies and magazines, and had basically become surfing's own Doris Day. O'Donell, 27 in 1964, hadn't yet started riding waves when Benson won Makaha, and was all but unknown outside her local beaches.

But roll the film (watch here and here) and O'Donell, to my eye anyway, is the more advanced—or at least more fluid and polished—of the two surfers. She was a fan of Bobby Brown, the young but doomed regularfooter from Cronulla, and it shows. Smooth as silk but not above throwing a spinner or two into the routine. O'Donell's win wasn't a fluke, in other words. Surfing World editor and filmmaker Bob Evans not only thought the same, he devoted six paragraphs in his contest write-up to the women's final—other publications dashed the women's event off in a line or two—lauding Benson and O'Donell both, but ending thus; "[O'Donell's] placement in the wave was ideal and her trimming and arching through the hollow sections was pretty to watch. Every ride these great girl riders made earned spontaneous applause, [but] Phyllis O'Donell was a decisive winner."

What happened after the contest, though, is just as remarkable. Phyllis smiled and took her trophy, drove home and—did nothing. In terms of career advancement, anyway. She continued to surf and compete. She entered the '64 Makaha contest. A few years later she would move briefly to Southern California to work for Dewey Weber Surfboards. She took third in the 1968 World Championships. But O'Donell might as well have invented the concept of life-work balance, and surfing for trophies and titles was in a gray area but leaning toward work. This quote, from an interview Phyllis did in 2000, makes the point:

In 1964, you became the first women's world champion. Did it change your life?

I was living in Banora Point [near the Queensland border] at that time, and it would have been more beneficial career-wise if I'd moved back to Sydney after winning the world title, but I wouldn’t do that. I had a good job in the local ten-pin bowling alley, where I was an assistant manager. I worked two days and three evenings each week so I could surf a lot. I wrote a surfing column for the Sunday Mail. So all told I was doing fine.

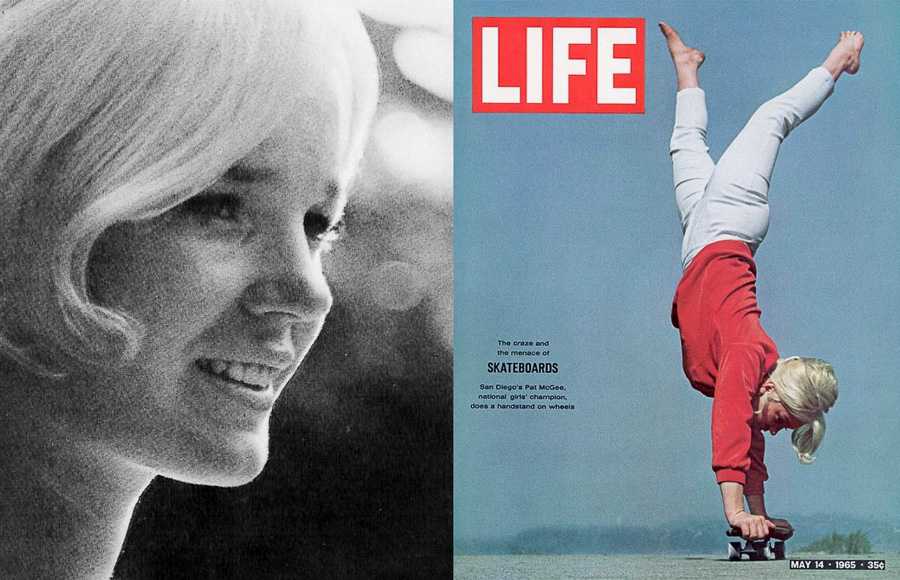

Pat McGee of San Diego also died last week, at age 79, from complications following a stroke. She is best remembered as the impeccably styled Capri-pants-wearing teenager hand-standing her way to Baby Boomer hearts across America as a 1965 Life magazine cover girl. Like nearly every board-crazed beach kid at the time, McGee was a surfer first—she started in '58, as a 7th-grader—and began skateboarding as a way to kill time when the waves were blown out. "You know how it was in the parking lot when there was no surf," she said in a 2017 Juice magazine interview. "Everyone was sitting around the car, smoking cigarettes and eating Twinkies. I was never one to sit on the beach or hang out in the car. I had to be doing something, I wasn’t ready to go home and do homework, so skateboarding was perfect." McGee was a good surfer but an even better skater. In the Santa Monica Civic parking lot, during the 1964 Los Angeles Surf Fair, she won the women's division of what the Los Angeles Times billed as the National Skateboard Championships.

Unlike Phyllis O'Donell, McGee very much wanted to see how far she could leverage her new title. The next step was obvious. Surfboard kingpin Hobie Alter, then charging his way into skating with a new line of Super Sufer skateboards and the hottest team on wheels, was just up the coast, in Dana Point. As Pat later recalled:

I took my plastic-gold trophy and my 8×10 glossy photos [and drove up] to see Hobie. I pulled into the shop, and said, “I want to be on your team.” It was 5 o’clock and Hobie was racing out the door in his suit with his folders and skateboards and all this stuff in his arms. He said, “I haven’t got time for this.” I said, “But look! I’m the Women’s National Skateboard Champion and I want to be on your team!” He said, “Can you babysit?”

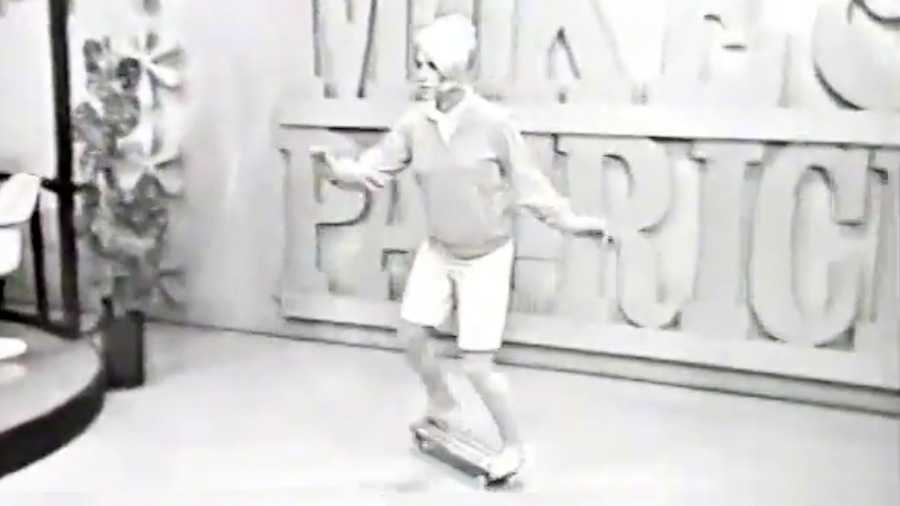

For the next 18 or so months, before the skate boom's near-overnight implosion, McGee was the world's highest-profile skater. (And the first female professional; Hobie paid her $250 a month.) Apart from the Life cover, she cruised barefoot across the stage on the Mike Douglas Show, taught Johnny Carson how to ride ("he has a lot of coordination and could really make a great skateboarder"), did three demos a day at Macy's in New York, with a limo driver to get her back to the hotel each night, and just before flying back home to California she glammed up in heels and pearls and a black cocktail dress for a turn on What's My Line.

The fact that McGee got all that attention air time doesn't tell the full story. It makes sense just for the fact of skateboarding being new and hip, and Pat being as gorgeous as she was skilled. Of course you'd want her on camera. But watch McGee on the Mike Douglas Show, and it's not the skating that sticks with you, or her beauty—it's the confidence and ease. She's not up there throwing zingers like the Fab Four, but Pat McGee's smiling self-assurance for sure has a Beatle-like quality. She's young and having a ball. She's cooler than anyone on stage, but her coolness is never wielded against the squares, it simply is, and Pat will in fact share it with you—just get the board pointed in the right direction, bend the knees, push off, and away you go.

Thanks for reading, everyone, and see you next week.

Matt

[Image grid, clockwise from top left: Hobie Super Surfer skateboard; Phyllis O'Donell surfing in Puerto Rico, 1968, photo by Barry Church; Jane Fonda on What's My Line; tenpin bowler in the mid-'60s; Los Angeles Surf Fair handbill from 1964; Pat McGee on the cover of the October 1965 issue of Skateboarder. 1964 World Championships, left to right: Heather Nicholson, Phyllis O'Donell, Linda Benson. Screengrabs of O'Donell during the finals. McGee's Life magazine cover, 1965. Detail from Los Angeles Surf Fair handbill. McGee and host John Daley on What's My Line. McGee on the Mike Douglas Show.]