SUNDAY JOINT, 7-11-2021: MAKING THE CASE FOR A TUBERIDING VOW OF SILENCE

Hey All,

Maybe it is a defense mechanism, but when somebody leads a long and full life I can’t feel too mournful when they die. Joe Quigg made it to 95, Greg Noll beat all odds to hit 84, and neither man left much on the table, so my response to their deaths is cliche but sincere, and goes something like great run, and you couldn’t ask for more. In Noll’s case, additionally, we are never not in the neighborhood of a salty tale, even while in memoriam, and I direct your attention to Mike Purpus’s alternative take on the Ricky James thumb story, in which Mike recalls staring in youthful delighted horror at the thumb-entombed paperweight, and later says to Ricky “I loved that thumb,” to which James replies, “Not as much as I did.”

Even with this kind of non-gloomy effort, though, we’ve just had back-to-back Sunday Joints in which death was front and center, so today let’s go hard in the opposite direction.

Four years ago I posted the EOS “perfect wave” entry, which in turn led to this perfect wave retrospective video, and the amazing fact that I was somehow able, with my Cliffs Notes-level Final Cut Pro skills, to stitch five versions of “This Magic Moment” into one sub-three-minute clip. The incredible Doc Pomus co-wrote “Magic” and if you’ve never heard of this feisty and soulful polio-bent Brill Building legend, you’ve listened to and loved dozens of his songs, and his own life story is just as affecting as his music. Watch this trailer for A.K.A. Doc Pomus, and see if this doc doesn’t go straight to your TV viewing on-deck circle. “I was never one of those happy cripples who stumbled around smiling and shiny-eyed trying to get the world to shake its head sadly in my direction,” Pomus says of his youthful self. “I was going to be the first heavyweight boxing champion on crutches. And I was going to make love to the most beautiful, exciting women in the world.” Pomus did not win the heavyweight title, but he otherwise turned a life founded in hardship into absolute magic.

In 2011 and 2012, Lewis Samuels did a series of articles for SURFER called Borrowed Boards, in which he traveled the world boardless and rode only what he was able to cadge from local surfers. Samuels at that point (and to this day) was best known for his viciously funny PostSurf blog. Borrowed Boards had its acerbic moments, but was far kinder and gentler than PostSurf, and at some point I will get around to posting the whole series, but here is Episode One. The relationship we have with our boards is fascinating to me, all the more so since our move to Seattle a decade ago, where I soon divested myself of all surfcraft, which I would have expected to be a sad passage, but instead felt very much like: great run and you couldn’t ask for more.

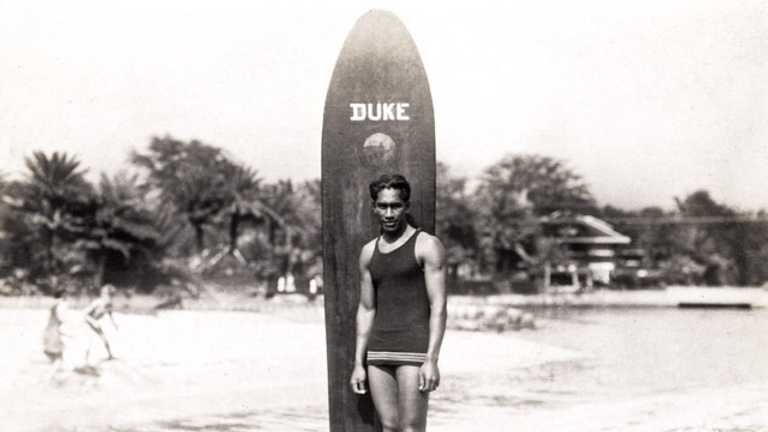

An attachment to surfboards in general is an entirely different thing than an attachment to a particular board, and this is actually where I wanted to steer the conversation because, unless you’re a museum owner or private collector, it is almost impossible—or pointless, I guess is the better word—to have a connection to one surfboard. They are too fragile, and have been since the late 1960s. That wasn’t always the case. In one of Tommy Zahn’s scrapbooks there is a 1950s photo of four boards propped against a wall in Waikiki somewhere. Tom Blake’s handwriting is scrawled on the photo, next to a 70-pound redwood that belonged to Duke Kahanamoku: “Duke’s 1905–1930.” He likely had other boards during that period, but apparently Duke rode that one board (see above, from 1912) for a quarter-century, and excuse me for being an old romantic but I wonder if a wooden board, simply because of its material, might imprint on a surfer more like a ship or canoe than a surfboard. Phil Edwards made his all-balsa “Baby” in 1957 or ’58, and rode it until 1962. George Downing did the same, the previous decade, with “Rocket.” Not counting guns, during my 40-plus-years period of hardcore surfing I don’t think I ever rode a board for more than a year. The owner satisfaction Duke and Edwards and Downing must have felt—well, the sport moved on and so did the surfer-surfboard relationship, and that’s just the wheel turning. But it must have been satisfying—grounding, even, although that is maybe a poor-chosen word in these circumstances—to have the same piece of equipment under your arm year after year.

And speaking of poorly-chosen words, I rediscovered this post from a few years back, on our collective and I think totally singular inability to describe in any meaningful way what it feels like to ride inside the tube. Watch here. The Rory Russell part kills, and I ended the blog post thus:

Dear Reader, I ask you to try and imagine what kind of zombie-level THC load was circulating through Rory Russell’s bloodstream when he said, on record, that a tuberide means “Mother Earth has you in her womb, in her cathedral, and you’re totally free, and she’s taking care of you.”

Writing about music is like dancing about architecture—not sure who said that, Dorothy Parker maybe—and evidence suggests that talking about the tube presents an even higher level of rhetorical difficulty. Rory’s comment reminds me that there’s a video interview somewhere out there with George Greenough, and when the greatest surf-world innovator ever born is asked what makes tuberiding so special, he thinks for a moment, then in a Rainman-meets-Spicoli voice replies, “Well, it’s really difficult.”

Like a brick through a cathedral window. As if we didn’t already have enough reason to love Greenough.

Thanks for reading, everybody, and see you next week!

Matt

[Photos: Peter Crawford, Surfing Heritage and Culture Center, Bruce Brown, Alby Falzon, Tom Blake]