"IN TRIM: LANCE CARSON," PROFILE BY PAUL HOLMES (1999)

Paul Holmes' profile on Lance Carton ran in the January 1999 issue of Longboard magazine. This version has been slightly edited.

* * *

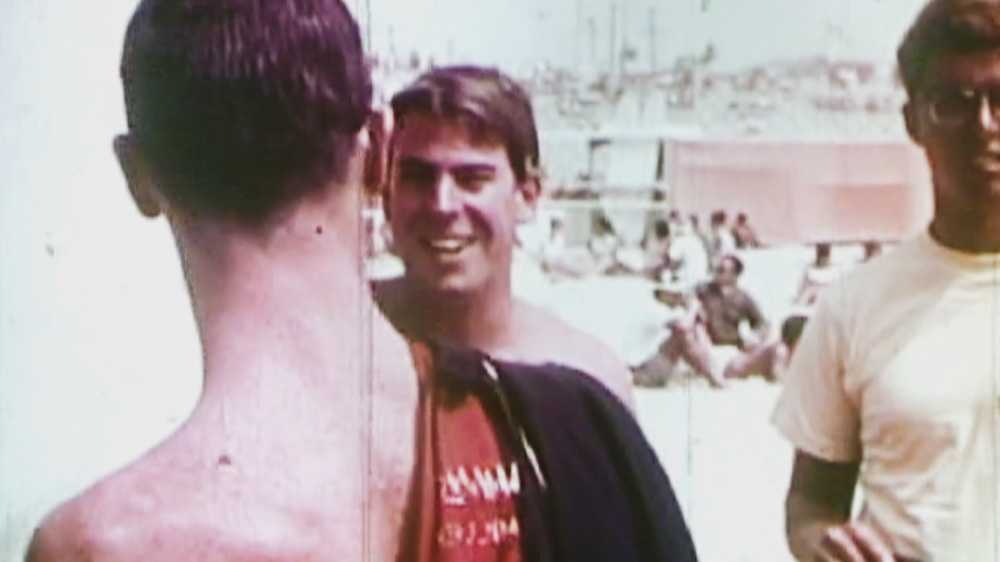

It's not easy being Lance Carson. At 55 years of age and one of the undisputed all-time greats in surfing's pantheon, he is genuinely stoked to be still involved in the sport through his board and T-shirt business, trading on a much-deserved reputation he earned during California's "classic" era of longboarding.

At the same time, he's a reluctant pitchman, uncomfortable promoting his wares at trade shows or in the media. As for his fame, it disturbs him to be hailed in the street or on the beach by people who recognize him but whom he does not know.

The past reveals a pattern of such contradictions. An extraordinary surfer by day, Carson was for years a raging rock 'n' roller at night. Those who knew him during the '60s agree that he could be charming and funny while sober, but outrageous and obnoxious when drunk—which by his own ready admission he was frequently.

Today, he still enthuses about surfing, and is excited and impressed by the new young generation of longboarders who have revived the classical style. But he doesn't ride much himself anymore because of crowds and an ongoing battle with skin cancers that makes him rightfully wary of the sun. On the one hand, Carson is deeply concerned about the environment. However, after a period trying to do something about it, he has become disillusioned about the mission and methods of environmental activist groups. Even in contemplating this article for Longboard, he has been by turns open, positive, and helpful, and then diffident, even paranoid, about its scope and tone. "I hate it when the media talks about legends," he said on completing the interview for this piece. "Legends are guys like Bob Simmons, LeRoy Grannis, Hoppy Swarts, and Velzy. We were just a bunch of guys who happened to be in the right place at a special time."

For a man whose soul clearly yearns for the peace and beauty found in nature, Lance Carson knows a lot about conflict—particularly that which lurks within. As his old boss, mentor, and sponsor Hap Jacobs puts it, "Lance was always a funny guy—kind of a Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde."

* * *

Carson grew up in Santa Monica and his bond with Malibu was forged at an early age. He had been a sickly infant—a spina bifida baby who'd undergone some gnarly medical procedures before his parents were told he'd need either spinal surgery or, he says, "some kind of therapy like exercise in water." In the late 1940s, the Carson family took regular drives out to Malibu, and young Lance was soon splashing in the small waves, unwittingly immersing himself in the "water therapy" that was to become the defining activity of his life. "I was fascinated with the surfers, this group of guys that hung together with their ukuleles and old beat up station wagons," he says. "I was just a little guy but I wanted to get my teeth into that. I thought it was so cool. At Malibu beach the sand was shiny white," recalls Carson. "At low tide you'd walk along and it squeaked under your feet. I can still feel the excitement of a Saturday or Sunday afternoon and what felt like a long drive way up the coast to watch the surfboard riders."

Lance's father, Donald, an engineering wizard in the embryonic aerospace industry, was fully supportive of the boy's new ambitions, and made Lance his first board—a hollow, ribbed, balsa bellyboard with a vee-bottom and foil dynamics that may have been inspired by the "Flying Wing" that Donald was working on at Northrop. "My dad and his buddies were all blue-collar, pencil-behind-the-ear kind of guys who'd sit around and design stuff—brainiacs," laughs Lance. "Every toy I had when I was a kid, except my bike, he made for me."

By the time Lance was six or seven, he was ready to move on to a stand-up board. Dale Velzy was the top boardmaker at Malibu and could often be found shaping balsa craft in the Pit during weekends. "We'd see him down there," says Carson, "A gnarly little guy, really buff, with a tattoo of a bulldog on his shoulder, wearing Japanese-style slaps, a pair of jeans with a half pint of rum sticking out of his back pocket, and a cigar stub stuck in the comer of his mouth. He was quite a surfer too. There'd be some UCLA college kids sitting around, and some of the actors of the time—Cliff Robertson, Peter Lawford, Lord Blears.

"1 just wanted to get out there," says Lance, "But my Dad was the kind of guy who wouldn't just go out and buy me stuff." Instead, the older Carson simply asked Velzy for the necessary technical information to make his son's board himself. "That's how we got to meet Velzy," says Lance. "He had this little shop down the road on PCH where he made driftwood furniture, and we went in there so my Dad could get some tips. Dale had all these pictures on the wall of guys riding giant Hawaiian waves. My Dad thought it was trick photography."

Regardless, Donald Carson learned what he needed to know. "He took our old Packard down to the L.A. harbor and loaded it with a bunch of balsa for $5 and drove it home. Then he went to an aircraft place downtown where you could get fiberglass. On weekends he'd spend his time getting clamps, gluing up the balsa, making me this board. For a little kid, it seemed like forever."

By the summer of 1950, the young Lance Carson had joined the ranks of the privileged few—on his balsa board, on his feet, on the waves at Malibu's pristine, peeling point.

* * *

The last time Lance Carson surfed Malibu was almost 18 months ago. It was a very different experience: "It was a big, pumping southern hemi swell. I drove up the coast and saw Topanga and Big Rock—giant—and I got that rush going again. Then the old story started—driving around Malibu, doing laps looking for a parking space and seeing all these big sets coming in. Malibu today is aggressive. You get all jacked up from the moment you start hassling for parking. When Malibu gets big the tension goes way up and everyone's trying to get the set waves, which is why it's often more fun surfing Malibu on smaller days. But this day the waves just kept coming and coming. It was like there were no lulls—eight-feet and pumping.

"Finally I get a parking spot down the end of the road, lock my car and walk down the beach, and all these guys are shouting out to me, "Hey Lance Carson, get out there, yadda-ya." As I paddle out, boards are flying everywhere, some with leashes some without, and all I can see is guys dropping in on each other, 20 guys on every wave. Everyone just dropping in, turning, kicking out and doing the same thing again on the next wave.

"A big set comes and I'm right on the outside but another guy takes off simultaneously. Suddenly he's yelling at me, 'Hey old man, you son-of-a-bitch. You old farts think you own Malibu!' So I kicked out. Well, the guy paddled back out and starts cussing at me, right in my face.

So I decided to paddle in and ride some inside waves. I got murdered. Every guy and his mother dropped in me. I was out less than 45 minutes. And that was the last time I surfed Malibu."

The story leaves Carson with a grimace and a fleeting but palpable shiver. Of disgust? Horror? Profound regret?

"I can't fight the crowd anymore," he continues, explaining why surfing at Malibu—and therefore wave-riding itself—is no longer a regular event in his life. "Plus you've got the lagoon and all the dirty water coming out of there. And the break has changed—it's shallower over toward the pier. Instead being a point from Second Point all the way down to the cove it's turning into a Third Point-to-the-end-of-the-pier beachbreak kind of thing. Sometimes a swell will clean it up, but it's not same. Then you've got all the people—some I know, some I've seen there over the years, some I don't know at all, who are always yelling stuff at me. And I guess everyone thinks it's cool to ride the same wave as Lance Carson or something."

It's a sad and savage indictment of the contemporary Malibu scene from a man who was once royalty at the spot. But the break in the early '50s was almost another world—so far removed from now it might as well be a distant universe. "There were people around back then, little groups of guys at Malibu and other spots—South Bay, San Onofre," Carson says. "But it always friendly and laid back. There was no aggression, guys were helpful to newcomers and for little guys like myself it was always, 'Yeah, kid, whaddya want to know?' Guys would surf up behind you and be shouting 'Come on, son, you can do it' And they'd help you up to your feet and hold you up, encourage you to actually surf. I was on top of the world. When the Malibu group was down on weekends I'd hang around the outer loop, pretending I was part of it. I felt like hot stuff."

* * *

By the middle of the 1950s, as Carson was growing into his teens, that "Malibu group" included board design pioneers like Joe Quigg, Matt Kivlin, and Dale Velzy, accomplished and experienced surfers like Buzzy Trent, Alan Gomes, and Les "Birdman" Williams, lifestyle innovators like Moondoggie and Tubesteak (soon to be celebrated in the original Gidget movie), and hot young riders pushing performance boundaries on the liberating new lightweight balsa and fiberglass "Malibu" boards—Miki Dora, Mickey Muñoz, and Mike Doyle among them.

"I knew all these guys' faces but I didn't know who they were until later on," says Carson. "I was kind of reserved as a kid, shy and quiet, so I wasn't about to go up and introduce myself and strike up a conversation. Dora was the first guy I remember having a lightweight board. You could tell because of the way he could whip that thing around. It was a new kind of turning. All the other guys still had that old Birdman style. Plus, Miki's boards looked different, like something out of a Venice art studio. [They] didn't have pinlines or panels. He had this one white board with paint-spattered gray rails, like he might have been doing an oil painting and had some paint left over. Up on the nose he'd painted the word 'Fiasco.' Nobody could figure that one out. And Miki had this new kind of stance and style—one foot back, turning and then stepping forward, not shuffling. This was the new hot-dogging, and I guess Phil Edwards was doing similar stuff down south.

"In the late '50s just before foam and Gidget, Dewey Weber and Freddy Pfahler came up from the South Bay and just ripped at Malibu. Dewey rode a red board and wore red trunks and his board was heavier. I always thought this was because he was so wound up it helped smooth him out. On a light board he was too fast. Dewey was doing stuff that Miki did, but 10 times quicker. And he was going all the way up to the nose—toes over. And I remember thinking, 'this is incredible. I love this. I've got to do it!'"

Carson is leaning forward, completely warmed up to the topic. "Noseriding is the epitome of longboard surfing," he continues. "That and the lost art of the stall, of which Phil Edwards was the master. But the first time you see someone noseriding you say to yourself 'What is that? How do you do that?' And you have to try it. At first, it's a matter of just getting up there and putting five over, and it feels so off-balance and out-of-control. Then you get to a point where you can do it with style, looking casual. Then it's about developing the skill to do it and actually control the board while you're up there."

It would not be long before Lance Carson did it better than anyone.

Terry Tracy, aka Tubesteak, aka Kahuna, was one of the elders at Malibu during the late '50s, and remembers watching Carson develop as a surfer. "I started noticing him around '57," says Tubesteak. "What set Lance apart was his attitude. Not good or bad. He just had a presence. He knew he was good."

But, Tracy adds, "he was a good kid, not a loudmouth. It's hard for a kid that age to hang out with surfers the likes of Dora, Doyle, Muñoz—guys who were 20, 21, 22 when he was only 14 or 15. But Lance was there. People knew he was there."

1959 was a pivotal time in Lance Carson's life and in surf history. Up to this point the sport had only been a summertime obsession—he was still dependent on his parents for rides to the beach. In '59, though, Carson turned 16. "I got my driver's license and a '40 Ford, exactly like the one in Big Wednesday. The downside is that surfing conflicted with school and homework. I was just getting by," he admits. "In high school I couldn't wait for three o'clock—I was outta there!"

It was around this time, too, that the first issue SURFER came out, and Huntington hosted the debut West Coast Surfing Championships. "Jack Haley won," remembers Carson. "I wasn't in it, but we drove down from Malibu to watch. It was like, 'What's this, a surfing contest? What's that all about?' We were surfing for the love of it. There was no thought of it leading to fame or a career."

This was also the year that Gidget hit the silver screen and surfing once and for all lost a hallmark of innocence—its capacity to be unselfconscious. "I went to see it in Santa Monica with my friend Rick Kreisler," says Carson. "And we snickered at just about everything— guys wearing cutoffs and all that stuff. It was cornball to us teenagers. We were cool. The guys on screen were not.

"In six months," he continues, "surfing just exploded. 1959 was the last uncrowded summer. Everyone was just getting foam boards. Kemp Aaberg, Bob Cooper, Johnny Fain, Dora—those late September afternoons after school with the fall low tides starting, I'd go up and surf Malibu with just six other guys out. Those were the days you could take off way outside First Point and make it across, all the way down to the end of The Wall, on the tip. That was perfection Malibu."

By the summer of '60 and '61, however, a new era had begun: "There were 200 guys out at First Point, and it was changed forever. We were left wondering, 'What's going on here? What happened to our precious surfing spot?' Of course, the upside is that here I am, 55 years old, and I have a business going out of this. Who woulda thunk it back then?"

Well, Hap Jacobs, for one, was a little ahead of the curve in that department. As demand for boards fired up California's surf shops, with the industry's hottest spot in LA's South Bay, Jacobs was quick to seize the opportunity, first by partnering up with master designer-shaper Dale Velzy, then by putting together a stellar surf team. Mike Doyle, Dora, Donald Takayama, Mike Purpus, Robert August, and of course Lance Carson, were among its luminous vanguard.

"I have all the great memories of the early '60s," says Carson, wistfully. "LeRoy Grannis started driving up to shoot photos, and Kemp Aaberg was getting all the locals together into the Malibu Surfing Association. Johnny Fain was doing his thing. All the beach parties at Zuma. We were a little group there, our own clique, dominating Malibu.

"And then hanging out around 22nd Street in Hermosa and being initiated into the Jacobs surf team and getting all the goodies—the team jacket and trunks, all that stuff. I was King of the Hill."

* * *

But there was another side to all of this motion and change, which also transformed the young Lance Carson. "As surfing exploded," he says, "I came out of my shell, out of my introverted self, and did a complete 180-degree turn. It was like something had been pent-up during my quiet, shy lifestyle growing up. It all broke loose.

"From 1960 to 1965 it was all about sneaking into beer bars in the South Bay with phony IDs. Hanging out with the 22nd Street crew, Henry Ford and Rodney Hatch and all the other Jacobs guys. Every weekend I'd be down there and we'd be wearing our team jackets and going out to party. The first time I ever saw the Beach Boys was down there. We'd heard that some guys who had a band were having a party so we went there to check it out. Well, it wasn't really rolling. There were just a couple of girls and there were these guys sitting in a comer strumming acoustic guitars. We took one look and said 'Oh, these guys aren't real surfers, they're from Hawthorne. They'll never make it. Let's go find a real party.' And we walked out. We were pretty cocky."

Of course, that band of acoustic-strumming quasi-surfers from landlocked Hawthorne did make it. Big time. By 1963, Gidget sequels and surf music had become a youth culture phenomenon that was sweeping the globe. By then Lance Carson, was not just a key Jacobs team member but also working (along with Robert August) in the Jacobs shop in Hermosa Beach, the core of cool.

But while Carson was having the time of his life, he still had moments of doubt about surfing's metamorphosis. "By this time, the beach was just crawling with gremmies," says Carson. "All these young guys in their Pendleton shirts and Sperry Topsiders and peroxide blond hair combed over to one side so it hung in their faces, trying to look like surfers even though real surfers didn't look that way. It was just like kids today with their tattoos and nose rings and colored hair. You have a few people who really live the punk lifestyle but the rest are just copycats. The gremmie thing was just like that. Gidget happened and the Beach Boys were singing about us, then you've got the surf mags and surf movies, and all of a sudden it was like 'where did all these people come from?'"

All those people, of course, were the general public whose leisure-time dollars were funding Carson's budding career. Not surprisingly, the emotional conflict extended there too. "Hap [Jacobs] would pay my entry into all these contests and I'd never want to go," says Lance with a sigh. "I never wanted to be out there in front of spectators. So Hap would say, 'Okay, okay, you don't want to enter, just put on your team jacket and trunks and walk up and down the beach.' So I'd be down at Trestles or Huntington or some other place and there'd be a south swell running, and I knew Malibu would be crunching and I wanted to be out there. I'd be looking at my watch, saying to Hap, 'Can I go now? Can I go now? Can I, please? I WANT TO GO SURF!' And he'd go 'No, just wait. Stay till two o'clock.' And I'd be like, 'AAAARGGHH!'"

Carson did enter a few contests. And hated them. "I had to sit out there in conditions I normally wouldn't bother with and try to do my best under this artificial setup with time limits. I had a hard time with all that. I remember being in an event in Malibu and I'm sitting outside all by myself, I turn around and see this huge crowd on the beach, and I'm thinking, 'Wow, all those peole are looking at me.' And I felt like I was under a microscope and it was really uncomfortable. I made a big deal out of something maybe I shouldn't have. But that was my reaction after growing up where surfing was a complete freedom thing."

I did win a few heats here and there. I'd get to the semifinals. But never made the finals. The only surfing trophy I ever won was a couple of years ago when I got inducted to the Surfing Hall of Fame. I wasn't even there to pick it up. Hap grabbed it on my behalf.

"I just wanted to surf the way I always had. I started surfing a certain way at a certain beach under certain conditions—with no crowds. What had gotten us to the team era was that we hadn't had any crowds," says Carson. "We didn't have to worry about guys snaking and dropping in. We could go out and practice our moves uninhibited, spend hours learning our craft with nobody getting in the way."

Today, Carson has second thoughts about how he handled his role during the Jacobs team years and says that if he had to do it again, "I might do things a little differently. There was a hypocrisy, because the whole team thing was an ego stroke," he concedes. "But I could have been a little less selfish and helped Hap out more. I just had a hard time going that extra mile and getting out there to really promote."

Hap laughs about that. He recalls all the classic magazine layouts featuring his star team rider. "Lance wasn't a contest guy. He didn't have anything to prove. And it wasn't a problem. He was real photogenic. He was pretty much the king out at Malibu—him and Dora. He was really good, so everyone wanted him to ride their boards. But Lance was really faithful to me."

Plus, Jacobs adds, Carson had other valuable skills: "Behind the counter in the shop, he was always dean cut, wearing a pressed, button-down shirt. He was good with people—and really good at giving them excuses why their boards weren't ready!"

Henry Ford, who worked for Jacobs as the team was being assembled, and was a lifeguard at Malibu from '63 to '69, agrees with his former boss: "Once in a decade a surfer comes along who is exceptional. Lance was the premier surfer at Malibu at that time. He had the style. He had the place wired. Nobody was any better at standing on the nose. He had impeccable wave knowledge, wave selection, and positioning. Dora and Fain and Doyle were all good, but they were always fighting, pushing and shoving. Not Lance. He just rode the wave, usually by himself.

"But he had a wild and crazy side," continues Ford. "I think he really got sidetracked with his rock 'n' roll thing."

That "thing" began in 1963. Carson was 21 at the time, had recently sidestepped the Vietnam draft for medical reasons (his history of spina bifida), and was drawn to the rock 'n' roll nightlife of L.A.'s beer joints and clubs. "There was a little place near Ocean Park and Main in Santa Monica called the Rip Tide which was always packed when the Dragons (a local band with a pro lineup] had their regular gig there on Friday and Saturday nights. So one night the cops came in and busted [Dragons' drummer] Mike Kowalski because he was underage. The guys asked me to sit in so they could finish the gig and I ended up playing with them for a couple of weeks till they could find another drummer. In the meantime, Steve Aaberg and Butch Simpson were looking for a drummer for a band they were starting. They saw me keeping a beat and singing and a couple of weeks later they asked me to come to Steve's house to rehearse. So we rehearsed for two weeks, went to Players in El Porto, did an audition, and got a gig. I was off to the races. I played music all through the '60s and '70s, did a couple of recordings, made a career and a living from it. So that was my life—surfing in the daytime, music and nightlife after dark. It was unique. I had this ultimate lifestyle."

Carson seemed on top of the world. Jacobs sold a ton of Lance Carson signature models and Lance learned a new skill— surfboard shaping—under the tutelage of a master craftsman. But the music part, as Henry Ford observed, sidelined some of the other surf career opportunities Carson may have had.

He remembers one in particular: "I was still working at the Jacobs shop with Robert August. I'd change into my band clothes after work, drive down the street and go play music at the Flying Jib. I happened to be there [in the shop] one day when Bruce Brown came in saying he was looking for a couple of surfers to do The Endless Summer. I had the offer right then and there to go around the world with Robert and Mike Hynson."

But, says Carson, aside from pursuing his musical career with the band, Spring Fever, he'd just met a girl and was contemplating getting married. "Plus," he says, "they didn't really know if they'd get any surf, so I kinda rationalized my way out of it. Robert went and I turned it down." Carson pauses, reflecting on the irony of not being part of the biggest surf media phenomenon of the decade. "Woulda, coulda, shoulda," he says. It's an expression he uses a lot.

It meant little if anything to him back then: "It was a confident, carefree time," he says of the early- and mid-'60s. "Drinking beer and chasing women. I was immortal. I could do no wrong."

Carson, however, was not fireproof and he did get burned. Tales of some of his more outrageous stunts—or their apocryphal elaborations—have become the stuff of surf folklore, been rendered as thinly-veiled fiction in surf magazines, been re-reported as surf history in the mainstream press (resulting in lawsuits from Carson), and even inspired scenes in the Hollywood surf movie classic Big Wednesday. Some of the more infamous: Posing as the hood ornament on a car careening around the parking lot of a Winchell's Donuts clad only in a fiendish grin and a glazed doughnut impaled on his you-know-what; playing matador with the Coast Highway traffic in Malibu; hanging naked from the balcony during a surf movie show; throwing a rock at a train passing by Cotton's Point; mooning anyone, everyone, any place, any time.

For the most part, though, it was not Carson's behavior on the beach or in the water that caused problems. Thinking that his status as a surfer gave him social carte blanche, and inflated with the bluster of alcohol, he began being met with unwelcoming receptions. “In the South Bay, I crashed parties and got thrown out by big football fraternity guys. I'd be yelling 'Hey, you can't do this! I'm Lance Carson, you know, the team rider guy from Malibu.' And they'd say 'We don't care who you are, you're not invited.'"

"There was another time in a bar, I was drunk and popped off and said something to the wrong people, and this black belt guy, Johnny Rice, grabbed me by the throat and threw me into street. I was told later I got off lightly but I couldn't talk for a week after he'd got me in that death-grip choke hold."

There were also tell-tale signs of potentially more serious repercussions. "I'd drive up to Santa Barbara to visit my pals Kemp Aaberg and Dick Natland who were at UCSB, and I'd drive 'em nuts. Kemp still tells me to this day how when they'd hear my '40 Ford pull up in the driveway they'd say 'Oh boy, here we go. Shut the books, there'll be no studying this weekend.' And I'd roll in going 'AAARRGH, where's the party...?' Then wake up the next morning and my car wouldn't be in driveway. I'd driven it through a hedge somewhere. One time I drove up in my VW van and found it in the Highway Patrol impound yard, full of broken glass and empty beer cans, because I'd rolled it down an embankment and just gotten out and walked back to the party. Somehow I never got busted and somehow I always walked away. My Dad could tell you more about those things. He was often the one who'd have to come and pick me up."

Of course none of this would have warranted even passing mention if Lance Carson had been a second-rate surfer, but he says, "I think all of those things made me a second-rate person. To this day, there are still people who think [the stories] are funny, but it's a part of my life that I regret. It didn't prove anything. It was obnoxious, lewd and lascivious. I wasn't the only one doing it. In fact, I was copying what I'd seen other guys doing. It was 'Oh, so this is the way we're supposed to carry on?' But I overstepped the bounds by wanting the attention, because I thought it would be cool. But it gave surfing a bad name, gave me a bad name, and in the case of the Cotton's incident] actually could've resulted in surf spots being shut down.

"I did a lot of good stuff when I was sober at beach, and got recognized for some of that, too. But I bit off more than I could chew when I was drunk, because of who I thought I was. When the party was over I just didn't know when to stop."

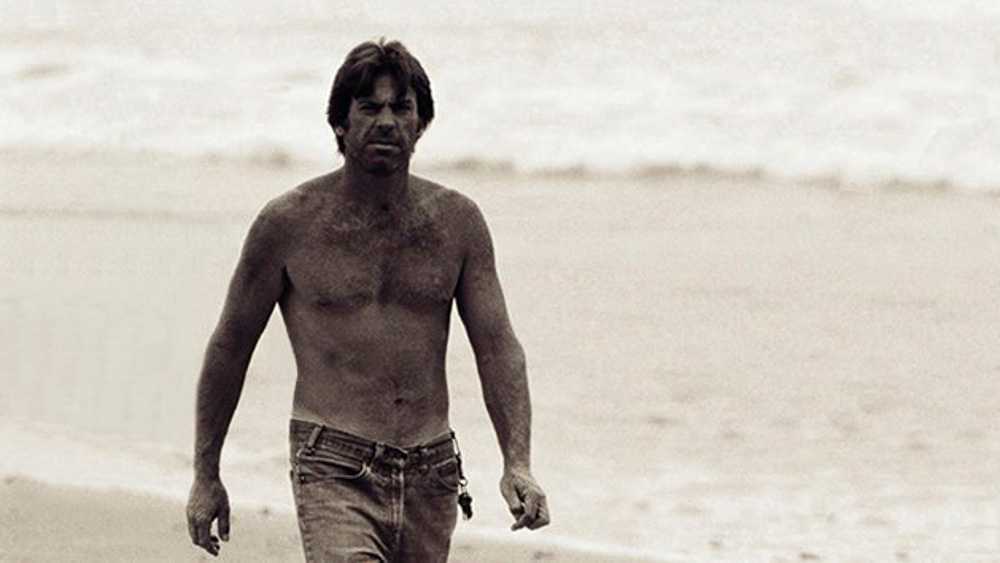

Things got a lot worse for Lance Carson before they began to get better. But it was not the partying that finally eclipsed his surfing career. Starting in late '66, after Nat Young's victory at the World Contest in San Diego, the decline in importance of noseriding—a large part of Carson's stock-in-trade—was set irreversibly in motion. When the late '60s ushered in the shortboard era, Carson's style, however polished, became an anachronism and his board designs became obsolete. "Longboards were getting more rocker, pinched rails, deep swept back fins. Things were just getting good when [Bob] McTavish came to California and changed everything," he says. "I was still a diehard longboarder. I was a stubborn old bloke who wouldn't make the transition. I kept riding the same old Jacobs signature models that I still have down in my garage."

As the '70s began—an era Carson calls "the dead zone" of California surfing—Carson found himself surfing less and drinking more, no longer in the spotlight, with no demand for his shapes.

In 1976, however, a couple of not unrelated events formed a potential silver lining to Carson's ominous cloud. "I was sitting at the Point with Denny Aaberg complaining about how things were so different from the old days and he suggested maybe I should start making boards again, that there were a few guys around who wanted longboards. So I quit the band, took some templates off my Jacobs signature models and made a few boards that summer."

Coincidentally, Aaberg was working with Hollywood screenwriter-director John Milius, developing the story for Big Wednesday. Milius had Aaberg interview Carson for added color and authenticity. Seen today, the parallels are plain between events in the life of Lance Carson and the story of Big Wednesday character Matt Johnson. (Further parallels with life events of Jan-Michael Vincent, who acted the part, are uncanny).

"John Milius had intentions of giving me a screen credit and I was going to be a stunt double for Gary Busey in the surfing scenes," says Carson. "But I was still drinking heavily, and just bloated and overweight. We went down to El Salvador and I bleached my hair to match Gary's, and I was down there with Gerry Lopez, Peter Townend, J Riddle, and Ian Cairns and everyone else [who had a part]. Well, I had problems on the set and I completely fell apart. They ended up having to ship me home on a plane and I almost had a nervous breakdown."

Shortly thereafter, Carson says, "Everything fell apart. I wasn't making boards, I'd quit the band, my wife of seven years had left me, and I knew I had to do something different. So I knocked on the door of a construction guy who lived in the same apartment house and I said, 'Hey man, I'm hurtin' and I need a job. Can you help me out?' And that's how I started hanging drywall, which I did for 12 years."

The way Carson tells it today leaves the impression that the change in his surf star status was almost a release, allowing him to become just another face in the lineup: "It was neat because I wasn't on a team, I wasn't making boards. I could just go to work and go surfing on my own time."

The most important transformation, though, had yet to come. "There's nothing wrong with being a God-fearing, moral person," says Carson from the sober watchtower of sobriety. "If people want to put me down for saying that, fine. But if you pursue the alternative lifestyle, sooner or later you will crash."

It took a long time for Carson to hit the wall. He remembers the exact day: Monday, September 10, 1979. "I was still doing drywall, still drinking," he says. "I had a big beer gut, big red puffy face, double chin. Pat Phinney was about to open the Baja Cantina at Malibu, and I was hanging drywall in the restaurant. The Sunkist Pro-Am contest was about to start and a lot of guys were in and out the door talking about it." From all the chatter, Carson learned that a mystery sponsor had put his name down for the "Celebrities" heat, and paid his entry fee. Two of the other contenders were Big Wednesday stars Jan-Michael Vincent and Gary Busey. It would be a great chance—the first in a long time—for Carson to give an exhibition at the spot he knew and surfed so well. And there'd be no crowd problem, for the duration of the heat at least. Media coverage and a little well-earned respect were virtually guaranteed. After years in "the dead zone" here was an opportunity for Carson to reconnect.

"On the Saturday morning I got in my Volkswagen van and was driving up to Malibu for my heat," recalls Carson. "It was a hot, sticky day and I was really hung over. I hit traffic right around Sunset, and as I was sitting there, stop and go, stop and go on Coast Highway, I said to myself, 'Oh, it's just another surf contest, what am I doing this for?' So I turned around and went home, went to the liquor store, got a case of beer, and sat in all weekend getting drunk.

"Monday comes around and I go back to work at the restaurant. Even though it was still unfinished, they'd held the after-contest party there and the cleanup was going on—paper plates and beer cans everywhere. And Pat Phinney walks in and says to me, 'You blew it. I was the one who entered you in the contest. I was trying to do anything to help get you out of here and get you back out there [in the surf at Malibu]. I opened the door and you wouldn't walk through. They were calling your name over the loudspeaker and you didn't show up. And here you are back at work, hanging drywall, after missing what could have been the best weekend of your life.'

"So I had to work all day and listen to all the stories of what happened, about how good the contest was, and how the party was so great. And I got so angry at myself that I decided, that's it—I'm not going to drink today. And I got through that day, and the next, and that became a week, then a month. And I just stuck with it."

Recovery, says Carson, probably saved his life, and he cites a few examples among many surfers and musicians with whom he could be "walking hand in hand," whose battle with booze lead to their untimely demise. These days he says he does not deny his past ("although," he adds, referring to some articles and books over the years, "everything I've been accused of—that's another matter") but tries to focus on the present and the future. "My spirituality; that's what I prefer to concentrate on."

These days that includes giving encouragement and trying to be a role model for the current crop of young surfers at Malibu. "They're a great bunch of kids," he says, "Unknown young longboard guys who ride the inside. They're cool."

One of them is Tyler Hatzikian, in whom Carson has found a kindred spirit despite the 30-year difference in their ages. "Tyler was born in the wrong era, " says Carson. "He would have fit right in at Malibu during my time."

For his part, Hatzikian says, "I have a lot of respect for Lance. Of course, I can only base my opinion on films I've of him at his peak, but he was definitely one of the top guys back then. Today, he often comes by and we get into deep discussions about the subtleties of riding and design. Lance believes it's all about trim and position and the line you take on the wave. I feel really fortunate to have him to talk to and learn from."

During the '80s, Carson's new outlook and focus compelled him to become an environmental activist on behalf of Malibu's beach and lagoon. "I was involved with [the late] Tom Pratte and the Surfrider Foundation because I was deeply concerned about what was happening at Malibu. But then Surfrider got bigger and it became all about having fundraisers to make money to tell us that the water is still dirty. And I said 'wait a minute' and kinda just backed away from the whole deal."

As the millennium draws near, apocalyptic visions and rapturous deliverance are on the minds of many peope—but there is no indication Carson is overly preoccupied in that regard. More mundane matters need to be taken care of, here and now—the starter motor that just failed in the cargo van he uses for deliveries; whether his father can look after his dog Opie, a hapa spaniel; a problem with the invetory size breakdowns in the next shipment of Lance Carson logo T-shirts for Japan.

Quietly, one day at a time, Carson is taking care of surf business, about half of it in the US and half in exports. "Right now, he says, "I'm getting into some replica balsa boards for the Japanese. These guys really study up on what went before, from materials to rails to rocker." Carson makes some 250-300 boards a year these days, each one shaped meticulously by the hand of the stylist whose logo can be traced back to a Rincon noseride some 40 years ago.

"But don't call us legends," says Carson. "I hate that. We were just a bunch of guys who happened to be in the right place at a very special time."