Chapter: 4

Ten-Year Boom

- Gidget the All-Powerful

- The Rebel Next Door

- Hobie vs Velzy vs the IRS

- Better Surfing Through Chemistry

- Summer on the Inside

- Surf Fashion, Lightly Salted

- Surfing the Newsstand

- Process of Elimination

- Oil City Showdown

- The Jazz Stylings of Phil Edwards

- Technicolor Surf Boom

- Heroes and Villains

- Blackball Blues

- Dick Dale, Destroyer of Amps

- Surfing in Five-Part Harmony

- Tokyo to Tel Aviv

- Flight of the Larrikin

- Bob Evans Means Business

- Midget Wins It All

- But Will it Play in New York?

- Houses of the Holy

- We Own the Sidewalks

- Beautiful from any Angle

- Duke's Big Contest

- Can You Handle the Penetrator?

- Girls, Don't Panic!

- David Nuuhiwa Walks on Water

- An Invincible Summer

An Invincible Summer

August, Hynson, Brown, LAX

Bruce Brown

John Whitmore, Elands Bay

Cape St Francis. Photo: Bruce Browne

An Invincible Summer

Newsweek said The Endless Summer was “not very well made,” and that filmmaker Bruce Brown “knew little about the niceties of shooting a documentary.” Then the magazine went ahead and named it one of the 10 best films of 1966 anyway. That's the kind of roll Brown and his movie were on.

Nothing better encapsulated the 1960s surf boom, nor more clearly marked its end, than The Endless Summer, Bruce Brown’s cheerful monster-sized crossover documentary hit. Filmed in 1963 at the very height of the boom, Endless Summer wasn’t released to general audiences until fall 1966, at which point the movie played like a coda for a era of the sport that, rather than being endless, vanished almost instantly.

Brown’s premise was simple—follow two California surfers around the world in search of the perfect wave—and the end result had a casualness that almost seemed offhand. To nonsurfers, Brown looked like a slightly aging gremmie who by some fluke had made a great first movie. But Endless Summer was in fact Brown’s sixth full-length work, and while he did come off as the very embodiment of California beach cool—blond, tan, and grinning, with, as writer Tom Wolfe described, a “Tom Sawyer little-boy roughneck look about him, like Bobby Kennedy”—he was also a driven and meticulous filmmaker.

Brown was a 19-year-old San Clemente surfer-lifeguard in 1957 when boardmaker Dale Velzy agreed to produce his debut movie. Velzy bought Brown a new Bolex camera and editing equipment, then peeled off $5,000 in expense money—enough to get Brown and his “cast” (five hot California surfers) to Hawaii for the winter and to cover all production costs. Brown read a how-to book on filmmaking during the flight to Honolulu. Back home two months later, unwilling to pay for a work print, Brown edited and spliced directly on the masters.

Brown’s first film, Slippery When Wet, toured Southern California beach cities in the second half of 1958, with a reel-to-reel soundtrack by jazzman Bud Shank and Brown himself doing live narration. Greg Noll, John Severson, and Bud Browne also had movies out that season; Slippery wasn’t necessarily better than the others, but Brown was by far the best narrator, and his film got the most laughs. He did a good job with his set-up shots: guys walking with their boards, conferring alongside the highway, playing cards back at their rented shack. Brown’s favorite portrait angle, lifted from old Olympic Games newsreels, was a front-lit head-and-shoulders shot taken from waist level, framing the surfer in a mildly worshipful upturned gaze.

Brown made another four movies, then in 1962 he put all his savings—$50,000—into what he hoped would be an upscale general-audience version of his earlier films. At first, the idea was to simply fly two star surfers to South Africa and go exploring for new breaks. The global “perfect wave” quest wasn’t born until Brown’s travel agent told him that he’d actually save $50 per ticket if he continued flying east around the world. Brown then realized that by crossing the equator, the summer season was doubled—The Endless Summer was picked as a title before Brown began filming. (As a rule, summer waves pale compared to winter waves, and Brown knew this as well as anybody. He also knew that The Endless Winter wasn’t going to bring ‘em out in Des Moines.)

Brown picked his two surfers well. Robert August was Endless Summer’s calm, dark-haired goofyfooter. Mike Hynson was the grinning regularfooter with the permanently slicked-back blond hair. August had just graduated as student-body president of his high school and hoped to become a dentist. Hynson was a weed-smoking, Benzedrine-popping wiseass on the run from the Army draft board. None of this came out in the movie. Both were likeable and authentic—genuine surfers as compared to, say, Moondoggie or Steamer Lane—but they were two-dimensional. Endless Summer wasn’t about Robert August and Mike Hynson; it was Brown’s own paean to surfing. The two stars were there only to move the action along from country to country, from one surf-related topic to the next, with Brown mediating the experience every step of the way.

Brown, August, and Hynson arrived at Los Angeles International Airport wearing suits and ties, as airplane passengers did in 1963. They traveled light. August and Hynson had one board each; Brown’s entire arsenal of camera gear, cases included, weighed less than a hundred pounds. There was no film crew. From California, over a four-month period, they circled the globe from west to east. They rode half-mile long waves in New Zealand, virgin reef surf in Senegal, and backwash swells in Tahiti. (Left on the cutting room floor: a scheduled two-day visit to the west coast of India, where the boards and camera gear were all impounded for the duration.) Hitting the most spectacular gusher in surf travel history, they also found what they'd gone looking for—the perfect wave—at a place called Cape St. Francis in South Africa.

* * *

Discovering good surf in South Africa wasn’t a total shocker—anyone looking at a map could see the potential. Making things a lot easier for Brown and company was the fact that Durban and Cape Town had both already taken to the sport in a big way.

Durban, especially, had every surf culture prerequisite in place: good waves, pleasant year-round weather, an enthusiastic beachgoing public, and a tradition of Australian-style surf lifesaving—wave skies and racing sixteens included—dating back to the late 1920s. Durban had sent a lifeguard team to Australia for the 1956 International Surf Carnival, and team members had all seen the Americans zipping around on their 10-foot Malibu boards. Returning home, the Durbanites began making what they called the “trick” board—a hollow timber-framed version of what the Americans were riding. Meanwhile, 800 miles to the southwest and completely unknown to the Durban surfers, a Cape Town crayfish diver named John Whitmore had already seen the California-style boards in a magazine article, and had built a few for himself and a few other local wave-riders.

A grinning Afrikaner with a pointy chin beard, Whitmore was also discovering new surf breaks almost by the week, first along the Cape Peninsula, then up the coast to Port Elizabeth and East London. In 1959, a roaming Hobie Surfboards employee named Dick Metz, near the end of a long worldwide journey, hitchhiked into Cape Town, where he met and befriended Whitmore. Through Metz’ connections, Whitmore became the South African distributor for Clark Foam and Surfer magazine, and by the time the Endless Summer group arrived in late 1963, he was the go-to man for anything having to do with South African surfing. Whitmore had already done a bit of surf-recon on the jutting Cape St. Francis peninsula, and it was his suggestion that Brown look for waves there.

In most respects, South Africa was like any other emerging '60s-era surf region, with a profuse first bloom of clubs and shops, magazines and competitions. Max Wetteland of Durban would represent South Africa in the 1964 World Surfing Championships and was a semifinalist. George Thomopolous and Tony Van Den Huevel would hold their own against the world’s best before the decade was over.

Apartheid racial policies had meanwhile come to define the country’s presence on the world stage. British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, with his Cape Town-delivered “wind of change” speech in 1960, launched what turned out to be a long, slow, deepening period of global isolation for South Africa, and the effects were already being felt in the sports community: not long after the Endless Summer crew left the country, South Africa was banned from the 1964 Olympics. In years to come, local surfers (and a good portion of surfers around the world, for that matter) would insist that sports in general, and surfing in particular, had nothing to do with politics. But surfing and apartheid were destined to cross paths, with results that often made surfers look shallow and ignorant. In 1966, Surfer ran a photo of a somber black teenager on a Durban beach with three board-carrying white surfers in the background, along with a caption noting that South Africa’s segregated beaches meant that “this native youngster can’t join [in] for a little fun in the surf.” Dozens of readers turned on the magazine. “Why don’t you guys think before your write such trash?” one subscriber wrote in a letter to the editor. “It only takes a thing like this to ruin a good magazine like yours,” another said. A Florida reader wrote: “Segregation can’t be that bad . . . the beaches are practically segregated here in Jacksonville, in that the whites stay with whites and the blacks with blacks . . . this way, everybody’s happy.”

But voices for change and equality were heard as well. After all, surfing was a Polynesian export, with the sublimely dark-brown Duke Kahanamoku recognized as the sport’s grand patriarch. For this reason alone surfing was perhaps less reflexively racist than 1960s America at large. Surfer published an editorial in response to what became a small flood of letters trigged by the 1966 Durban beach photo, saying that “human dignity and equality [should be a] concern for all of us,” and that the magazine would bring to light “any force that would hamper any surfer from enjoying the sport anywhere in the world.” Nobody dropped their board and rushed off to march in Alabama. But the sport would continue to now and again take an honorable stand against racism.

* * *

As a movie, Endless Summer exists in its own completely unpoliticized world—although Brown at one point cuts to a panning shot of dolphins swimming through a Durban lineup while throwing in a mild gag: “Sharks and porpoises have yet to integrate in South Africa.” He’d polished the line, along the rest of the voice-over script, during Endless Summer’s debut tour in 1964, when Brown screened the movie himself and did live narration.

Technically the movie at that point was still a work in progress, and Brown often made small edits from one showing to the next, but the basic sequences were finished. So was all the subcontracted production work. A San Clemente band named the Sandals recorded the soundtrack, which included “Theme from Endless Summer,” a minor-key surf instrumental masterpiece containing a harmonica bridge that would, in decades to come, make Baby Boom surfers tear up with nostalgia. John Van Hamersveld, a moddish 22-year-old Art Center graduate, created the Endless Summer poster; a Pop Art gem featured Brown, August, and Hynson in black silhouette against a blazing Day-Glo sunset—it became the sport’s inescapable image, just as “Endless Summer” itself became the sport’s inescapable tagline.

Even in its 1964 barnstorming beta version, Endless Summer already skewed toward a general audience. Brown opened the film with a 10-minute primer explaining the different forms of surfing. Throughout the movie, he showed plenty of non-surf-celebrities: beginners in Ghana, intermediates in South Africa, bellyboarding natives in Tahiti. Surf films had never been vulgar or graphic, but Endless Summer was the cleanest yet, with no trace of the cigarettes, wine bottles, and funky living quarters as seen in movies like Slippery When Wet. Two or three lingering bikini shots—that was as racy as Endless Summer got. Brown might have expected some eye-rolling from hardcore surfers at what was obviously a softening of the surf movie genre. But they loved it. So what if Endless Summer was G-rated—the sport was being described back to them, correctly and in full, and it felt great.

* * *

Endless Summer presented real surfers traveling to real locations, and it couldn’t be described as anything other than a documentary. Except Brown didn’t really care about documenting, in any meaningful sense, his four-month trip around the world. He didn’t really care about documenting the sport in general, for that matter. What Brown wanted to do—what he did flawlessly—was present the look and feel of surfing in its best moments. In a way, Endless Summer was an impressionist work, and Brown was craftsman enough to arrange, conceal, accent, and outright invent as required.

Endless Summer's untruths were mostly small and thrown in for dramatic effect, like the overstated 50-50 odds that a surfer caught on the wrong side of Durban’s netted beaches would be killed by a shark. Some of the inventions were longer and more elaborate, including the perfect wave discovery at Cape St. Francis. In the film, Brown, Hynson, and August cross miles of sun-blasted dunes to finally stand gaping—along with the audience—before a heavenly vista of empty, sparkling-blue, right-breaking point surf. Hyson and August rush forward into the best waves of their lives. Brown, narrating, tells us that they’d started the day not expecting to find any surf. “We didn’t even know if we’d find the water.” But here it was, Brown continued, as the glory continued to play out onscreen, and the Cape St. Francis surf by Brown's estimation was probably this good 300 days a year.

In truth, Brown and company began their stay on the Cape by checking into a beachfront hostel. The following morning, Hynson noticed a likely-looking break a mile or so to the south—the perfect wave, as it turned out—walked up by himself, starting riding, and was soon joined by the others. Ninety minutes later, the waves shut down. And that was it. With nothing to surf the next day, Brown insisted that they all spent two or three hours marching up and down the dunes for the camera; he'd determined overnight that the movie would need an ex post facto opening sequence to set up their big score. The remark about Cape St. Francis surf being good 300 days a year?Brown made that up a few months later, while writing the voice over.

An interesting thing happened when Hynson finally told the real Cape St. Francis story in 1993. Nobody cared. The waves themselves were real, if nowhere near as consistent as Brown claimed, and the beachfront really was made up of dunes. But it wasn’t that. Every surfer, at some rare and transcendent moment, will hit upon the perfect wave—even if it’s just a fluke afternoon at their local shorebreak. In the editing room, Brown arranged events to highlight a universally shared surfing dream. It wasn’t deceit, exactly, in that it felt real. Surfers accepted Brown's version of events not as a lie, but as a gift.

* * *

Wowing the gremlins and femlins with his debut version of Endless Summer in 1964, driving from beach town to beach town, Elks Club to VFW hall, was no big deal for Brown. He'd had been impressing that audience for years. Booking the film into 8,000 theaters across the country and earning raves from Time and The New Yorker—that was another story. Indeed, when Brown hit this high mark, it was and remains one of the great achievements in the history of independent film.

How this happened is nearly as good a story as the round-the-world trip itself. Brown needed a distribution deal for Endless Summer, and to that end he had to prove that the film could play to a general audience. He took it to the Sunset Theater in Wichita, Kansas, America’s most landlocked city, and there, over the course of two snowbound weeks in early 1965, a new voiced-dubbed edition of Endless Summer outgrossed both My Fair Lady and The Great Race. When distributors still weren’t convinced, Brown spent $50,000 to have the film blown up from 16mm to 35mm, kicked in another $25,000 in promotions, and arranged for what amounted to Endless Summer’s third debut, in June 1966, this time at a funky Lower Manhattan theater called Kips Bay. The Gilgo Beach crew who’d seen Endless Summer during its 1964 barnstorm tour earlier lined up again to buy tickets—except now they were outnumbered by non-surfers. The Kips Bay engagement was a smash hit, Brown got a sweet deal with Cinema V Distributing, and Endless Summer finally went nationwide.

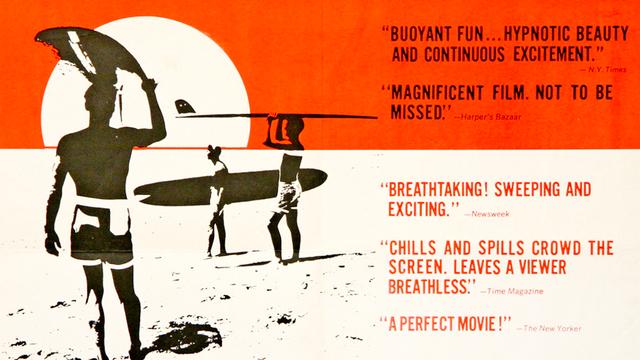

The New York Times lauded the film for its “hypnotic beauty and almost continuous excitement.” Time called it “an epic.” Sounding glad for the chance to test-drive some teen lingo, The New Yorker closed its review with: “Great background music. Great movie. Out of sight.” Newsweek sounded a rare note of criticism, saying the movie was “not very well made,” and that Brown “knew little about the niceties of shooting a documentary.” Then the reviewer went ahead and named it one of the ten best films of 1966 anyway. That’s the kind of roll Brown and his movie were on. (Oscar voters ignored Endless Summer for that year’s Academy Awards, but Brown came back to win a Best Documentary nomination for his 1971 motorcycle film On Any Sunday.)

Audiences turned out in big numbers for Endless Summer well into 1967; at Kips Bay, the movie played continuously for nine months. In mid-June 1967, the Times reported that Brown had just earned his first million—serious money at a time when the average American suburban household income was about $7,500—and that Columbia Pictures would be releasing the film overseas. It was nearly impossible to not be charmed by Endless Summer. Robert August, working behind the counter at Jacobs Surfboards when the film crossed crossed over, later said that ticket sales benefited from student protests, race riots, and the Vietnam war. “Everything was controversial. Everybody was tense. And Bruce’s movie was a big time-out. It was like, ‘Let’s just have fun for awhile.’”

Brown himself was cheerful and casual during his Endless Summer promotional appearances on the Tonight Show and Jack Paar. But as he told the Times, he was “tired of talking about surfing” and had no plans to make a sequel. He kept his word. Brown was a wealthy 30-year-old with a wife and three kids, and by the end the 1967 he’d quit working. For two years he rode dirt bikes, trolled for broadbill swordfish in his new Boston Whaler, and hung around the house with his family.

And yet again, his timing was perfect. What Endless Summer reviewers and distributors didn’t know in 1967, what movie-going audiences from Flagstaff to Rochester didn’t know—and what Brown certainly did know—was that surfing had gone into pupation and was already beginning to emerge, in a strobe-lit cloud of pot smoke, as a radically different sport. Thirty-year-olds weren’t especially welcome. Brown was one of the few surfers from his generation to exit entirely on his own terms.

The Endless Summer, the surf boom’s last and best manifestation, would eventually be granted everlasting cinematic life in revival houses, on cable TV, on VHS and DVD. Eventually it would be added to the United States National Film Registry. But in the early post-boom era, it went from relevant to obsolete nearly overnight. All that 1963-shot footage had looked passably modern three years later, when the film opened nationwide. By late 1967, for hardcore surfers at least, Endless Summer already looked as if it were set in amber.