SUNDAY JOINT, 5-22-2022: BLACK IS THE NEW RED

Hey All,

I cut way back on the screentime after posting that Make or Break rave last month, and not until yesterday did I get around to the season finale, which of course takes place at Lowers and ends with Carissa Moore and Gabriel Medina crowned as 2021 WCT world champs. I remain a Make or Break fan. But the show did not, for me anyway, build or improve on the first two episodes—in fact it seemed less sure of itself as it went. The clichés started creeping in. The WCT’s Wall of Positive Noise was, if not resurrected, no longer under siege. Filipe Toledo’s title-snatching aversion to heavy waves is mentioned but not examined. The Surf Ranch Pro—despised by WCT fans and pros alike, but a golden invitation to a talk about the promise and existential dread of wavepools—is offered as just another tour stop. None of the surfers in episodes two through seven, which the exception of Medina, are anywhere near as interesting as Tyler Wright was in episode one. Ditto for the contests themselves—as you’d expect, since the CT now begins at Pipeline, which is a dumb move by the WSL, but that’s a topic for another day. I think the Make or Break creatives will fall back and make improvements, and I’m very much looking forward to Season Two. But I’ve adjusted my Season One score from a low 9 to a high 7.

All that said, two things in the Make or Break season finale stood out. First, the waves at Lowers looked so much better than I recall from watching the live stream. Bigger and smoother and 100% fair, in that everybody got a fair shot, nobody was screwed by the conditions. I still believe Finals Day deserves a better venue than Trestles—but Trestles, last year, did its part.

Second, Filipe Toledo’s all-black Sharp Eye quad, even while just resting in the sand, looked like a panther sprinting through a gallery of Diebenkorn landscapes while listening to Charli XCX’s “Pink Diamond.”

Stylish, fast, and bold. Five pounds of bespoke flat-black confidence.

Black is, of course, an aggressively impractical color for a surfboard. Or it was, anyway. Two minutes in the summer sun and you’ve got melted wax all over the car upholstery, towel, boardbag. Another hour, if it’s hot enough, and the glass will bubble off the foam like cheese on a skillet, and if somebody out there tells me an overheated PU board will eventually spontaneously combust and leave nothing but a crater I will not be surprised. Carbon-wrapped EPS-core surfboards not only solved the bubble problem, but the boards are light, strong, and whip-fast. Plus they look like a million bucks compressed into a flying dagger. Most black boards are made at Dark Arts in San Diego, which I was expecting to be huge and high tech, but looks instead like the same three guys from every hardcore board factory between here and Dale Velzy’s garage. Owner Justin Ternes admits that the company can “add colors to the boards, to reduce sun exposure,” but then states the obvious: “I recommend staying black; black is best.”

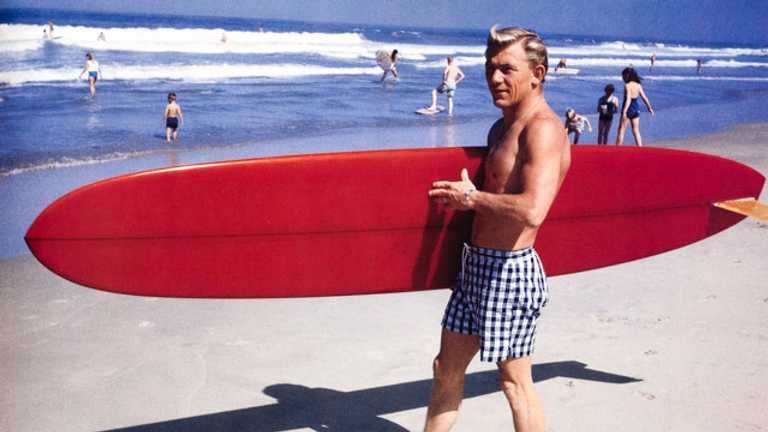

Red used to be the best. Board-fashion-wise, what Filipe is doing today with black—and not just Filipe, but John Florence, Tatiana Weston-Webb, and Kanoa Igarashi, among others—is what other great statement-making surfers have traditionally done with red. Barry Kanaiaupuni and Tiger Espere on the North Shore in 1969. Dewey Weber at Hermosa. And maybe reddest of all—Laura Blears and her 1975 Playboy Lightning Bolt.

My new favorite red-board surfer is Joseph “Scooter Boy” Kaopuiki, who lit up Waikiki in the 1940s and ’50s on an 11-foot-long fire-engine red hollow board, which he rode like a Benzedrine-huffing finalist in the Savoy Ballroom lindy hop dance-off. Grady Timmons, in his essential book Waikiki Beachboy, said this about Kaopuiki:

Most beachboys were not big-wave riders. They were exhibitionists, their giant surfboards their stage. It was far more common to see a beachboy on a small wave, riding in while standing on his head, or carrying a woman in his arms, much as he might carry her across a threshold. The old-style surfboards were well suited for such antics. They were as big as beds—at least ten feet in length—[and] a surfer could improvise endlessly. Few were better than Scooter Boy Kaopuiki.

When beachboys talk about Scooter Boy, they have trouble finding words to describe him adequately. Coming up short in mid-sentence, they will suddenly jump on a picnic table or begin running up and down their living-room floor, demonstrating how Scooter Boy rode a hollow board. “Scooter Boy had that board flying all over the wave,” said Buffalo Keaulana. “He would run to the front, jump up in the air, and land on the nose, kicking the water from the nose so that the board would spin right around.”

Scooter Boy, a fireman by trade in addition to working as a beachboy, was small and ripped—he boxed as a welterweight and was said to be the best broken-field runner in Hawaii’s wildly popular Barefoot Football League. He was also stubborn. In the mid-’50s, years after board styles had moved on, Kaopuiki was the only person in the Makaha International Surfing Championships riding a hollow board; the same one he’d had for years.

Incredibly, given his foot speed and gyroscopic balance, Kaopuiki—who just three months earlier had taken up hang gliding with his wife—died in 1985 after slipping from a bridge during a hike. He was 74. A flotilla of canoes took Kaopuiki’s ashes through the Waikiki surf where he’d kicked up his heels years earlier, red trunks matching his red board, and put him to rest just beyond the lineup.

Thanks for reading, and see you next week.

Matt

PS: Red is best or black is best, take your pick. But red and black together as a rule does not work. Red, black and white, however, works very well, too well, so well that you cannot avoid looking as if you’re riding for the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Try again.

PPS: Scooter Boy, great as he was, was often the second-most famous creature riding that huge hollow board, literally and figuratively behind his poi-dog Sandy.

PPPS: Professional pride demands that I direct your attention to some beautiful high-performance black surfboards that caught everyone’s eye long before Dark Arts came along. Top to bottom: Paul Gebauer, Ben Aipa, Reno Abellira.

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: Dark Arts surfboard; Tiger Espere at Sunset by Mark Sandvig; Filipe Toledo at Lowers; Dewey and Caryl Weber by LeRoy Grannis; Rory Russell, 1980 Lightning Bolt ad; Scooter Boy Kaopuiki by Bud Browne. Filipe Toledo at Lowers. Weber by Grannis. Scooter Boy by Browne. Paul Gebauer at Sunset by John Severson. Ben Aipa at Ala Moana. Reno Abellira at 1970 World Championships.]